The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has been heralded as a “turning point” in US climate politics, ushering in a new era of “industrial policy” and putting the national economy on track toward “net zero” carbon emissions by 2050. As the signature climate legislation of the Biden administration, the IRA bill is no doubt substantial in terms of the breadth of public funds earmarked to stimulate the burgeoning renewable and ‘low carbon’ industries. This includes nearly $400 billion in federal climate-related funding, as well as the creation of a massive $250 billion loan program under the Department of Energy to upgrade, repurpose, and replace energy infrastructure.

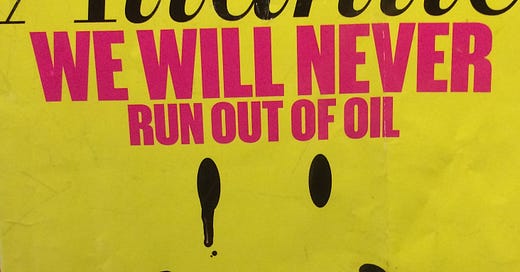

While, as the White House has recently touted, the IRA bill may represent dollar for dollar the “largest investment in clean energy and climate action ever,” the extent to which this “turning point” contributes to an energy transition in any meaningful sense is far less clear. Things are certainly happening—major new buildouts of solar and wind farms, the 45Q-boosted “gold rush” of carbon capture proposals, and the slow but significant electrification of the US fleet. But, in sheer quantitative terms, an ‘energy transition’ worthy of the name is not equivalent to simply the expansion of green investments but denotes an aggregate line: the drawing down of the ever-increasing stock of carbon in the atmosphere. A number of different vectors, at a variety of different scales, contribute to this aggregate, many of which remain downplayed or entirely ignored in rosy declarations that we are finally moving toward decarbonizing the national economy.

As seemingly obvious as it is consistently under-analyzed, this includes the most important and most directly countervailing force pitted against ‘energy transition’—ongoing oil and gas extraction. Of course, after its passing, there were many questions raised, mostly by environmentalists, about fossil fuel-favorable contingencies buried in the IRA bill. In particular, there is the 45Q tax credit boost, which subsidizes the recycling of captured carbon into “enhanced oil recovery” at $60 per captured metric ton of carbon (and $85 per metric ton for permanent storage). While I have already written about the glaring limits to an effective, national CCS buildout (and especially direct air capture), I will have more reason to return to this very important policy change below. But first, a brief note must be made about the other notorious mandate, included at the behest of Senator Joe Manchin, that federal oil and gas leasing must be offered prior to solar and wind leasing.

Amidst worries last year that the IRA bill “[handcuffed] renewable energy development to massive new oil and gas extraction,” much of the guffawing of such “apocalypticism” amounted to misleading and frankly irresponsible speculation about years-off conditions of oil and gas markets. Oil historian Gregory Brew, for instance, was quoted in a Slate article reminding us that “investment in new offshore projects has been declining over the last five years.” This neglects to note that, 1.) extrapolation of any long-term trend in offshore exploration beguiles the very erratic, volatile nature of oil and gas investments, and 2.) the rider in question, § 50265, does not just include the mandate for offshore oil and gas leasing but also guarantees priority for oil and gas leasing onshore as well. It is also worth noting that this claim echoes similar ones made by industry and market analysts, that the North American upstream oil and gas sector was afflicted by “chronic underinvestment.”

One year out, what is the status of this supposed underinvestment in oil and gas? Well, at present, the United States currently leads the world in upcoming oil and gas projects, including fresh new investments by BP and Shell in the Gulf of Mexico, and is expected to produce more oil by the end of 2023 than ever. Hence, whether the IRA bill is effective in actually scaling down emissions at all still remains to be seen. More importantly, what also escapes assessments like that of Dr. Brew is that federal leasing has more than one function in the oil and gas industry. Leases, in particular onshore leases, are not bought solely for the purpose of direct exploration and production but are often retained as options to hedge oilfield development elsewhere. Portfolio diversification, particularly in proved undeveloped (PUD) reserves, plays well with investors and can help boost a firm’s market value and borrowing base. Depending on the overall capital costs of a given firm, productive utilization of new lines of credit can more than offset the cost of holding an undeveloped lease, while entirely avoiding royalty payouts—new increased, as also included in the IRA bill—which would flow from oilfield development in federal lands or waters.

Federal leases thus do not need to be actually utilized; they simply need to be auctioned to boost the ‘financial health’ of the industry. Even still, the prioritization which §50265 affords oil and gas interests over renewables is still supposed to be eclipsed by two ostensibly more positive and powerful features of the IRA bill. First, there are the billions of dollars in subsidies earmarked for carbon dioxide removal, in particular the aforementioned 45Q tax credit boost for carbon capture. Obviously, the idea here is to address ongoing emissions sourced in fossil fuel consumption not directly by curbing them or by managing end user demand but by counteracting them with the expansion of finance for ‘negative emissions’ technologies. Speaking once again in terms of the vectoral components involved, it is not clear at all that this will be sufficient to net positively toward energy transition. Rather, the IRA bill seems to me to be a tax-based framework designed to mask the swell of carbon stock driving climate change in an increasingly convoluted carbon accounting regime.

Now, ‘energy transition’ proper—that is, again, a drawdown in the rate of increase of atmospheric carbon stock—is supposed to be proven in the amplification of this first vector by a second one: the release of new subsidies for green and low-carbon technology which, it is said, will render the latter more and more competitive with fossil fuel-based products and eventually replace them. However, as a very important paper by Richard York, “Why Petroleum Did Not Save the Whales,” ought to remind us, technological pathways, particularly those mediated by capital, are never so predictable. As he vividly demonstrates, the replacement of blubber with petroleum as an illuminant at the turn of the 20th-century did not kill off the whaling industry but in fact led to its acceleration. Modern whaling techniques were developed on the basis of the use of fossil fuels, in particular faster steamships and fossil-fuel powered air compressors to keep large whale carcasses floating long enough to hull onshore. The most whales that were ever killed in one year occurred during the 20th-century, after the rise to market dominance of fossil fuel substitutes. It was not the market but the political imposition of an antimarket moratorium which ended the whaling industry—one which only arrived after whale populations had been driven to the brink of extinction, hence after the industry had already lost much of its prospect for future profits.

The lesson here should be clear: as a component of the world economy as dynamic and relational as any other, the oil and gas industry is by no means simply keeling over in light of policy support for competing energy sources. It is getting more technologically innovative and more financially resilient in order to remain competitive with its potential substitutes. More than this, in fact, the IRA bill is quite explicitly designed not for the phaseout of oil and gas but to bring them on board to the discourse and politics of ‘energy transition’. Again, I refer to the 45Q tax credit boost, with which industry figures have been positively elated to endorse, as the sort of ‘policy support’ it needs to ‘lower its carbon intensity’. The result of this boost to 45Q, alongside new subsidies for blue hydrogen production, does not at all present a restriction on future fossil fuel extraction. Quite the opposite, it massages the impact which increased competition from renewables will likely have on the industry.

Short of any compulsion to do otherwise, it seems obvious to me that the oil industry will continue to pursue its own interests. This means not only expanding its ‘core business’, as it has always done, but also, now with the “policy support” of the IRA bill, carving out a place for itself within the dynamic contours and expectations of energy transition. Indeed, the oil industry has in recent years hastened to adopt ‘climate solutions’ as if they were always its own flesh and blood (‘we have been capturing carbon for 50 years!’). At industry events, they now ape the basic demands made of energy transition advocates: the need for energy abundance, the need for the rapid deployment of negative emissions technology, the need for governmental action (qua “policy support”). And I can tell you they are quickly learning to deploy the language of “just transition,” a “circular economy,” and “inclusive capitalism.”

Of course, the exploitation of progressive rhetoric in the name of conserving deleterious social and ecological conditions is nothing new. Inherent to the self-expansion of capital is not only the transcendence of its barriers—be them political, economic, cultural, or ecological—but also their valorization. However, this particular co-optation points us to something novel regarding our ‘current conjuncture’. Industry figures have grown to recognize themselves as key, indispensable accomplices in ‘energy transition’, as wielding, exclusively, the requisite resources, expertise, and economic power to bring it about. After decades of denial of climate change, the fossil fuel industry is now assuming the paradoxical role of mediating a ‘transition’ away from itself.

In turn, precisely as contemporaneous with this about face, we see conjured the appearance of a “turning point” in US climate politics. Underpinning romantic recollections of the IRA bill as the curtailed if authentic culmination of over a decade of struggle waged by progressives, we can see, at the very same time, the deepening and strengthening of the oil industry as grand mediator of the ‘energy transition’. If the IRA bill seems ‘progressive,’ it does so only from one side—only, that is, if one ignores the growing negativity of the ‘vector’ of oil and gas interests. Far from a “turning point,” then, the IRA bill represents an increase in the ‘implied volatility’ inherent to this precarious equilibrium mystifyingly called ‘energy transition’. Not a circle but a spiral; not a transition but a swelling stasis.