The first issue of the Society of Exploration Geophysicists’ flagship journal Geophysics, published in 1936, contains three entangled, interfering faces of geophysical reason. The first is the much derided but persistent informal reason, as showcased in the issue’s opening article, “Black Magic in Geophysical Prospecting.” In a tone both jovial and bitter, the author Ludwig Blau (Humble Oil) recollects a series of anecdotes about superstitious devices which had been deployed across the country to prospect for oil, mocked as “doodle bugs.” Such apparatuses came in all forms, from the humble divining rod to elaborate steam-powered machines adorned with bells, whistles, and buttons which the operator would ride in as he roamed around the oil patch. Although these devices were of dubious validity—this is precisely what made them doodle bugs—Blau insisted that it was nevertheless crucial to document them so as to more efficiently explain to lay oil men the unscientific foundations of their purported functionality.

Now, I describe this mode of geophysical reasoning as informal in order to emphasize its localized, improvisational character. Further, while there is precedent for these superstitious devices dating back to the early days of the oil industry, I specifically refer to this as a geophysical mode of reasoning, precisely because, at the time of Blau’s writing, many of these practitioners had adopted their justifications to ape extant geophysical theory. Indeed, “divining rods” had long been thought by their practitioners to be premised on naturally occurring phenomena, such as the purported physical correspondence between the ‘electrical field’ of the rod and that of hidden underground deposits of minerals, water, and oil. In turn, as scientific understanding of such phenomena improved, geophysical principles were increasingly cited as justification for the functioning of doodle bugs. The primary example referenced by Blau, in fact, was a device built by a “young man who discovered that the short electromagnetic waves emanating from oil and gas sands could be caused to modulate the wave of a radio transmitter” (1936, p. 7). And, as I investigate further in my dissertation, industry archives are populated with numerous letters from doodle buggers ‘talking scientifically’ in the attempt to convince formal prospectors to collaborate in what the latter understood as mutually compatible commercial endeavors. No doubt, both the preponderance and similitude of doodle bugs during the 1920s and 1930s is one important reason why Blau’s article inaugurates Geophysics.

But what is important to understand is that these informal geophysical methods remained, precisely, non-formalizable—that is, they were unable to be decontextualized and reconfigured into abstract scientific principles. Consistently, in other words, a condition of their functioning was that their operations could not efficiently be communicated from person to person, save through arcane methods of apprenticeship. In addition to their geophysical justification, their success demanded an occult knowledge of their practitioners, whose bodies and knowhow were an indispensable feature of the validity of the doodle bug.

By contrast, the second face which appears in the first issue of Geophysics is that of formal reason. This is by far the dominant mode of reasoning expressed in nearly every other article: M.M. Slotnick charts velocity spreads in order to provide a better method for determining the depth of seismic records, C.O. Swanson calibrates dip needle readouts to map the geometry of magnetic formations in the subsurface. Such reasoning, indeed, grounds the motivation of the Society of Exploration Geophysicists for starting Geophysics: to formally communicate research across geologists and geophysicists, most of whom either consulted for or directly worked in the industry. Instructed by their employers to keep their findings secret, announcements of developments in exploration methods, e.g. in trade journals, remained remarkably vague through the 1920s heyday of exploration geophysics. At the same time, there were no exploration geophysics textbooks or formal training courses, and, until the 1940s, there were only two American schools granting degrees in exploration geophysics: St. Louis University and the Colorado School of Mines. Hence, Geophysics emerged to correct for the dearth of publicly available research in exploration geophysics at the time.

In contrast to informal reasoning, formal reasoning relies on what Geoffrey Bowker calls in Science on the Run (1994) the “destruction of historical context.” Precisely the validity of geophysical reasoning, on its formal face, becomes the removal from view of its origins in contingency. This is what makes its claims not only communicable across space and time but also proprietary, that is, patentable. Key to defending one’s originality against competing researchers is to demonstrate that the contingencies of the new discovery or method didn’t matter, that one or the other was a novel finding of “pure science.” The destruction of historical context thus moves in a contradictory fashion: on the one hand, it provides a common language of geophysical science across its practitioners as it simultaneously intensifies its privation. Formal reasoning, in turn, can be characterized as the governance of empirical observation by these abstract and communicable forms which, cleansed of their original context, have become simultaneously a priori scientific principles and the wellspring of privatized scientific discoveries.

Now, to stress, these faces of geophysical reason are not dichotomous; once again, they are and remain entangled: just as the doodle bugger mimics a more formal geophysical reason in the attempt to ground the scientific legitimacy of his devices, the properly scientific prospector by no means ascends to some Archimedean point in the formalization of geophysical reason, even if that is what is ultimately claimed. In hailing the primacy of formal reason, the discipline of geophysical science will strive to minimize the importance of contingency but it will always fail to do so. Any geophysicist working in the industry today will tell you there is much still owed to hunches and dumb luck in the art of subsurface exploration. Contingency is not eliminated, only mediated differently.

But there is one more face of reason to discuss, one which mediates contingency in an entirely different way than either informal or formal reason. For lack of a better term, I will refer to this face of reason as informatic reason. Like the first two faces, it pervades the entire history of oil prospecting. But it is best crystallized in the issue’s fifth article, “A New Reflection System with Controlled Directional Sensitivity,” written by the idiosyncratic prospector and serial inventor Frank Rieber. Now, what is interesting to me here is how Rieber opens with a rejection of the “idealized reflection system” upon which formal seismological reason and existing seismic instrumentation are based, precisely in light of the absence of any field encounter with such “ideal conditions” (1936, p. 97). Thus, what is recognized here is that the concrete geological conditions corresponding to the success or failure of a reflection seismographic survey do not correspond to existing conceptual abstractions.

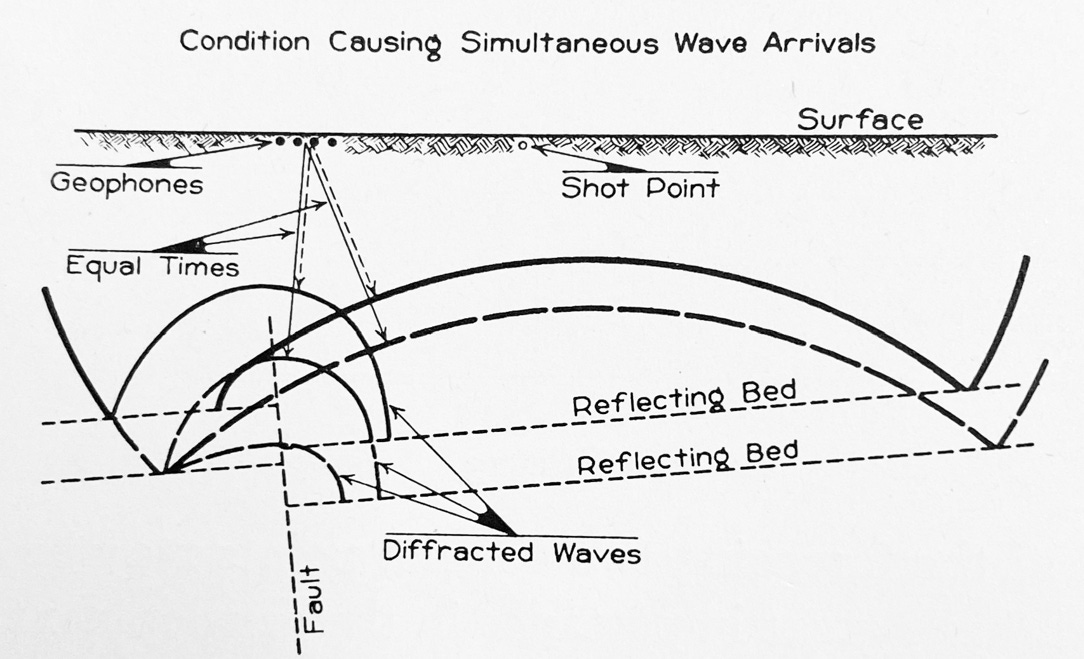

In particular, what Rieber is concerned with is the problem of overlapping “wave trains,” or portions of the seismic wave (i.e. the shock wave emitted by a detonation of dynamite) which arrive at the recording device from different directions simultaneously. Given the existing method of reflection seismic interpretation, which associates amplitude peaks with interfaces between rock beds, overlapping wave trains will lead to interference, distorting amplitude magnitudes and hence obscuring the true signal of the geometry of the subsurface. A variety of geological conditions could result in this occurrence—the one Rieber is especially concerned with, as shown below, is faulting.

Now, none of this is news to practicing geophysicists of the day, but what is different, and what will prove Rieber to be so controversial within the discipline, is the method he proposed to interpret earth-wave interactions. At the center of this “new reflection method” was a machine he dubbed the Geo-Sonograph. The novelty of this machine was that it parsed seismic traces—that is, amplitude readouts recorded by seismometers—for incoming angle of direction, namely, by passing the traces underneath a slit filter and compounding the resulting values. As he discovered, setting a different angle for the slit filter across the traces will yield different resulting compounded amplitudes, and the task for Rieber was to find experimentally the slit filter which corresponded with the highest peak amplitude to, from there, determine the incoming direction. If there were two local peak amplitudes, this according to Rieber pointed to the presence of two overlapping wave trains arriving at different incoming angles. Thus, from recordings of amplitude magnitude alone, it appeared as if the Geo-Sonograph was able to infer the paths of seismic traces.

At the annual Society for Exploration Geophysicists meeting in Los Angeles on March 18, 1937, Lewis Morton Mott-Smith, a physicist at Rice University, strongly rebuked Rieber’s invention. Among other damning criticisms, Mott-Smith insisted the intended results were physically impossible, as the wave diffracted at the edge of a fault could not possibly have the requisite energy to affect a recording at the surface, which was hundreds of feet above the interface. In response, Rieber lambasts Mott-Smith for his mistaken appeal to “classical physics.” The most important point, for Rieber, was that his method worked, regardless of its purported geophysical impossibility: he had discovered faults, subsequently verified through drilling, and he had been able to interpreted overlapping wave trains to discover the depth of interfaces underground. (Decades later, Rieber’s solution would, in fact, be vindicated: the method of slant stacking he pioneered is a fundamental component of seismic interpretation to this day.)

All of this is foundational stuff in the history of science, no doubt: a classic, even stereotypical standoff between pure and industrial science, deductive and inductive reasoning. However, what I want to stress in the notion of informatic reason is the difference in Rieber’s process of experimentation versus either the doodle buggers or other formal scientific prospectors of his time. Unlike formal reason, the justifications underlying Rieber’s Geo-Sonograph are clearly dependent upon the contingencies and contradictions of field experience, e.g. the fault lines he probes in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Paradoxically, however, and quite unlike informal reason, Rieber’s justifications are entirely abstract from the subsurface; they are conditioned by the possibility of data manipulation within his machine. This, in fact, is precisely what Mott-Smith found so off-putting: he warned that all of these distortions amounted to “machine noise” which did nothing but remove the signal further and further from any meaningful correspondence with its geological origin.

In one sense, Mott-Smith is entirely correct. The synthetic signals produced by Rieber’s Geo-Sonograph are composite, technological artifacts. In another sense, however, what Mott-Smith overlooks is that technological mediation is one component of an entirely novel “reflection system” proposed by Rieber which spans ‘real’ and virtual worlds. He is not, in other words, just providing a new analyzer to interpret seismic signals in the same way as before; he is presupposing a completely different, far more variable, contingent, and even chaotic conceptual model of the subsurface than the one to which Mott-Smith adheres. It is indeed a different spatial ontology entirely: no longer the empty Cartesian space of oscillating harmonic waves but a spatiality which recognizes and procedurally reflects upon its own artifactuality. Indeed, in my view, Rieber here backs up against something quite like the data space of modern computing, and hence of modern machine learning algorithms, which provide thoroughly relational and inferential answers when tasked with solving ‘real-world’ problems.

To that end, it is worth noting that throughout his life Rieber had stressed the importance of mass data collection for the advancement of exploration seismography. When the seismic method seemed to be reaching the end of its utility as US oilfield discovery rates began to decline in the 1940s, Rieber had insisted the issue was not at all that there was a lack of oil left to be found. Rather, underlying the declining rates of discovery was a purely technical-quantitative challenge: sampling rates were too sparse to yield the resolution necessary to develop more sophisticated techniques of seismic prospecting. To find more oil, the industry needed more data—and better means of interpreting it. It is my belief that it is precisely this burgeoning strength of informatic reason recognized by Rieber quite early on, indeed prior to the introduction of modern computers, which carries oil prospecting into the “Information Age.”