Prices, Value, and Oil - Revisiting the Negative WTI Price Crash

Or, what is a Yuányóu Bǎo?

(This was originally published on here a few years ago, but I took it down for one reason or another. Anyway, it is now back up.)

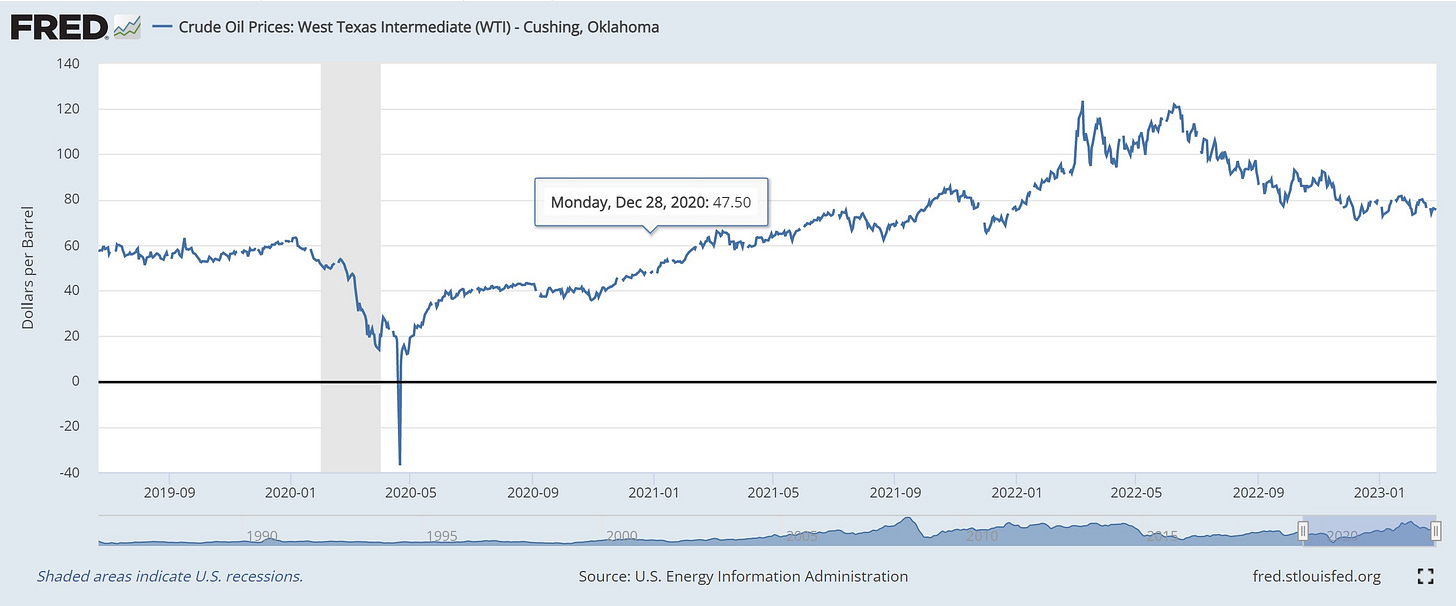

Over the course of a little under two years, the price of WTI front month contracts ranged from -$37.63/bbl to $123.70/bbl (respectively, the market close prices for April 20, 2020, and March 8, 2022). It seems to me obvious that this situation exposes the limits of the explanatory power of ‘supply and demand’. And yet, reviewing financial press of the time, one can see the most delusional mental contortions exercised in efforts to ham fist these extreme bounds into a conventional (or rather, imaginary) analysis of ‘market fundamentals’.

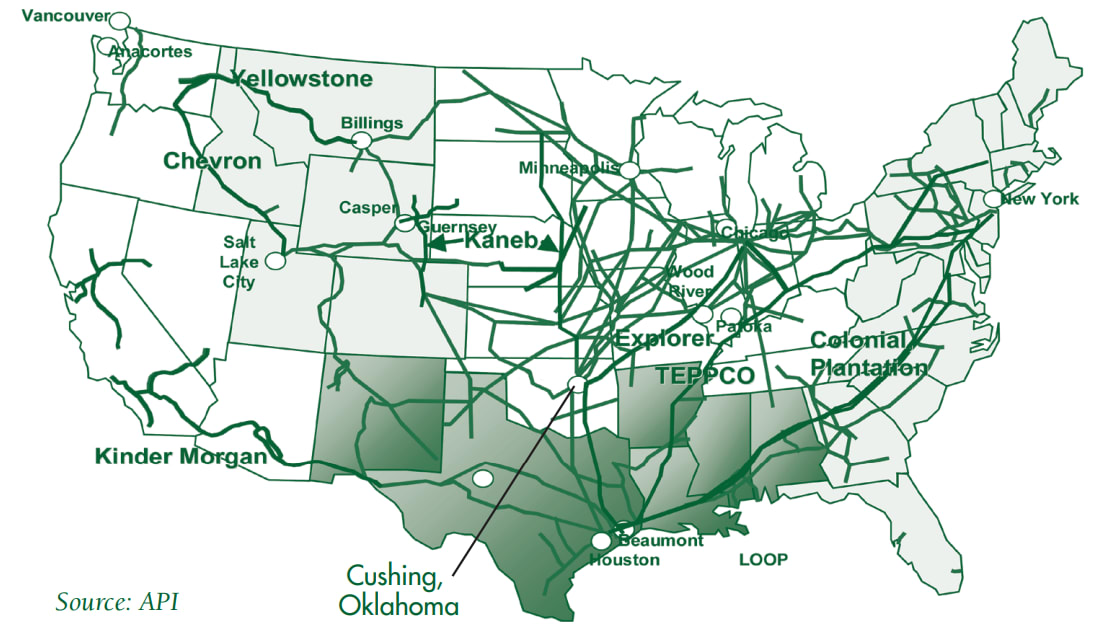

With respect to the lower bound, the Financial Times cited “analysts” who believed “lack of available storage capacity” at Cushing, Oklahoma (the meeting point for physical delivery of WTI-benchmarked crude oil) was the primary culprit for the historic dip of WTI front months into negative prices. Reportedly, this was the result of the convergence of two trends. First came the steep drop in demand as the COVID-19 pandemic imposed a slowdown in economic activity across the world. This, in turn, is supposed to have applied downward pressure on crude oil prices throughout March and most of April.

The second trend was that more and more commercial oil traders were electing to keep their inventory stored at Cushing: rather than sell crude to refineries in the near-term at rapidly falling prices, traders elected to hold onto the oil, taking on the additional carrying cost in order to sell contracts for long-dated delivery which, at the time, were settling at much higher prices. These two trends reinforced one another: news reports of storage capacity at Cushing nearing its limit pushed the front month price down even further, and mounting panic finally erupted in a fire sale on April 20. On that day—importantly, as I will note below, one day prior to expiration of the May contract—any remaining long traders with open positions but without any means to exercise their contracts and take physical delivery were forced to realize huge losses in order to take those obligations off their books.

As for the higher price bound, much ado had been made in 2020-2022 of the so-called “commodities supercycle.” Here, it is predicted a structural imbalance in increasing demand for a host of primary commodities is set to overwhelm supply, pushing prices upward across the “commodity complex.” This imbalance is supposed to be especially acute in the oil industry, the derivative products of which serve as inputs for nearly every other industrial sector. Jeff Currie, head of Commodities Research at Goldman Sachs, has been sounding the alarm about this since early 2021. Of course, the 2021-2022 oil price spike helped buttress this narrative immensely, with the added tension of Russia, a major oil exporter, embroiled in war with Ukraine precisely as the global economy sees recovery in demand following the shock of the pandemic. This led many oil market analysts in the year following to become heavily bullish on oil prices remaining above $100/bbl in the medium- to long-term, insofar as sustained or rising demand, chronic North American “underinvestment,” and regional “price wars” remain the order of the day in the global oil trade.

These two explanations of crude oil price movement for the lower and upper bound, respectively, seem to me unsatisfying. For one, it makes little sense to say that the anticipation of a 30% demand drop at the onset of the pandemic could send WTI crude to crash into negative prices, even when considering the carrying cost and potential for bottleneck at Cushing. Among other things, arbitrageurs should have been able to buy the front month contracts, take delivery, and hold the oil offsite at quite lucrative rates of return with minimal risk well before the -$38/bbl bottom. Why didn’t this happen?

Secondly, again, recent economic slowdown combined with rising capital costs, thanks to hikes in interest rates at the Fed, had (at the very least) halted any supposed impact of a “commodities supercycle” on oil prices. Indeed, despite all of the handwringing about underinvestment in North American upstream exploration and production, WTI crude prices have since fallen as low as 35% off their 2022 peak.

How does one explain such extreme price movements in such a short amount of time? Are we really to believe that these prices respect rational and perfectly-informed expectations about the market, or even more absurdly that supply and demand have actually fluctuated to an extent that would justify such volatility?

The conditions of possibility of negative oil prices

So, let’s first turn to the infamous May 2020 WTI contracts. It is important to clarify three things about futures contracts immediately. First, the day of expiry for a monthly WTI future is set to the third business day before the 25th calendar day of the month preceding the delivery month—unless the 25th calendar day is not a business day; if that is the case, the date of expiry is 4 business days prior to that date. A mouthful. What it means is that, for the infamous May 2020 futures, this date of expiry was April 21 (a Tuesday, the 25th being a Saturday). Either way, this buffer is specified so that commercial traders can arrange pipeline scheduling for physical delivery for the next month. Typically, non-commercial traders (i.e. those who are merely trading paper and thus have no intention of sending or receiving physical oil) avoid holding contracts into the date of expiry because on that day they will be obliged to take on physical delivery. Most will have long since "rolled over" their positions into the next month's contract.1

A second point of clarification is that by “oil futures price” I am referring to the price at which the future delivery of oil is purchased or sold. In the press, the most commonly cited price for "WTI crude oil" is the market price for the front month contract, i.e. the monthly contract with the nearest date to expiry. This is different than the “spot” or “cash” price of the WTI, which typically refers to the benchmark price of oil marked for “immediate” delivery (in reality, the delivery is not in fact "immediate" but set within a scheduling window of several up to as many as 60 days). What is important to know is that spot markets have very low trading volumes relative to the total amount of oil traded on any given day, with over 90% of physical oil being traded through medium- and long-term forward and futures contracts.2 This means the price signal of the spot market is not particularly reliable. The bulk of the oil trade being arranged through long-term contracts also means that forwardness is fundamental feature of the oil trade, and hence that the temporal separation of purchase, sale, and delivery is mediated primarily by the prices of the oil futures markets.

Third, and related to the second point, there are market prices of course not just for the front month but also for each consecutive month's contract exchanged on NYMEX. This trading calendar extends 11 years into the future. Even though contracts with expiries in the nearest few months comprise the vast majority of trading volume on the exchange, these illiquid long-dated futures prices are often mistaken as if they give meaningful information about what spot prices in the future will be. Indeed, and despite the fact that futures prices have been proven to be worse predictors of future spot prices than no-change forecasts, traders routinely assume as much about futures prices. Given the central importance of expectations of future price movement, oil traders will thus incorporate this pseudo-information into pricing models which, in turn, actively shape their trading behaviors in the present.

Ultimately, it is the forwardness inherent to the oil trade and the mediation of this forwardness through futures markets which explains why commercial traders were incentivized to hoard oil at Cushing. To explain, it will help to further elaborate the conventional narrative sketched out above: The destruction in demand for oil at the onset of the pandemic, combined with expectations about its future rebound, were taken to be ‘priced in’ to the futures market through what is known as “contango”, where near-dated contracts were being sold at discount to far-dated contracts. Commercial traders can (and will) take advantage of this upward price curve by utilizing a trading strategy called a “calendar spread,” through which they buy near-term, lower-price futures contracts and sell long-term, higher-priced futures contracts. This allows them to eliminate any future price risk and immediately lock in as profit the difference between the sale and purchase of their futures contract (less the carrying cost, i.e. the cost of storage and transportation).

The ability to profit off of hoarding, however, has ‘real-world’ limits: taking oil out of circulation and marking it for future delivery also means that the physical market increasingly risks no longer fulfilling its first-order function—that is, clearing inventory at Cushing. This is precisely what is said to have played out in April 2020. Storage capacity had been reported to be reaching critical levels, and those still holding front month contracts on the day before expiry (April 20) appeared to be caught scrambling trying to find any way to close their position, fearing that they would be unable to physically take May delivery at Cushing.

Now, while this narrative isn’t ‘wrong’ per se, it overlooks much about the specific mechanics of the WTI futures market and the distinct characteristics of its different participants. Both of these factors are necessary to explain the negative price crash on April 20, 2020.

First, as Ilya Bouchouev has shown, the contango in the oil market was already accelerating by February, back when Cushing inventories were at less than 50% of total capacity utilization, which was well below the historical norm. The CFTC claimed in a November 2020 report that storage at Cushing was “nearing capacity” by March 2020. During that month, storage utilization was in fact hovering around 50-55%—ranging from lower to roughly equivalent to the capacity utilization at the time of the CFTC report, which had been written in the context of a markedly different pricing environment (see Figure 1 above). While April did see capacity utilization peak above 80%, this is as close as inventories ever came to topping tanks at Cushing. Hence, the relationship between contango and storage capacity utilization is not linear, with markets ‘pricing in’ storage risk and participants automatically responding. Rather, it is more of a spiraling feedback loop, where the expectations of an imminent physical bottleneck at Cushing, combined with the availability of hedging strategies like the aforementioned calendar spread, incentivized hoarding which lowered the price, which incentivized more hoarding, which lowered the price...

Now let’s turn to those who were holding May 2020 contracts and were purportedly panicked about the bottleneck at Cushing. While there was some legitimate concern that any remaining marginal storage capacity would not be available to those who had not already contracted with storage operators, it is hard to believe a professional trader could not have found a solution for significantly less than the losses ultimately realized on April 20. Cushing is certainly a very large and centrally important site of storage, but it is only one location in a much more geographically integrated North American oil market than this panic about ‘topping tanks’ would have one believe. Of course, transportation and storage costs present a significant barrier here, but, as stated at the beginning, not one so thick that arbitrageurs wouldn’t be able to buy the remaining May 2020 futures, take delivery offsite, and realize a quick profit simply by selling the next month’s futures—which, notably, never dipped into negative prices. This, indeed, would have been the economically ‘rational’ thing for any counterparty with the funds to do the moment asks started heading south of $0/bbl. Why was there no arbitrage?

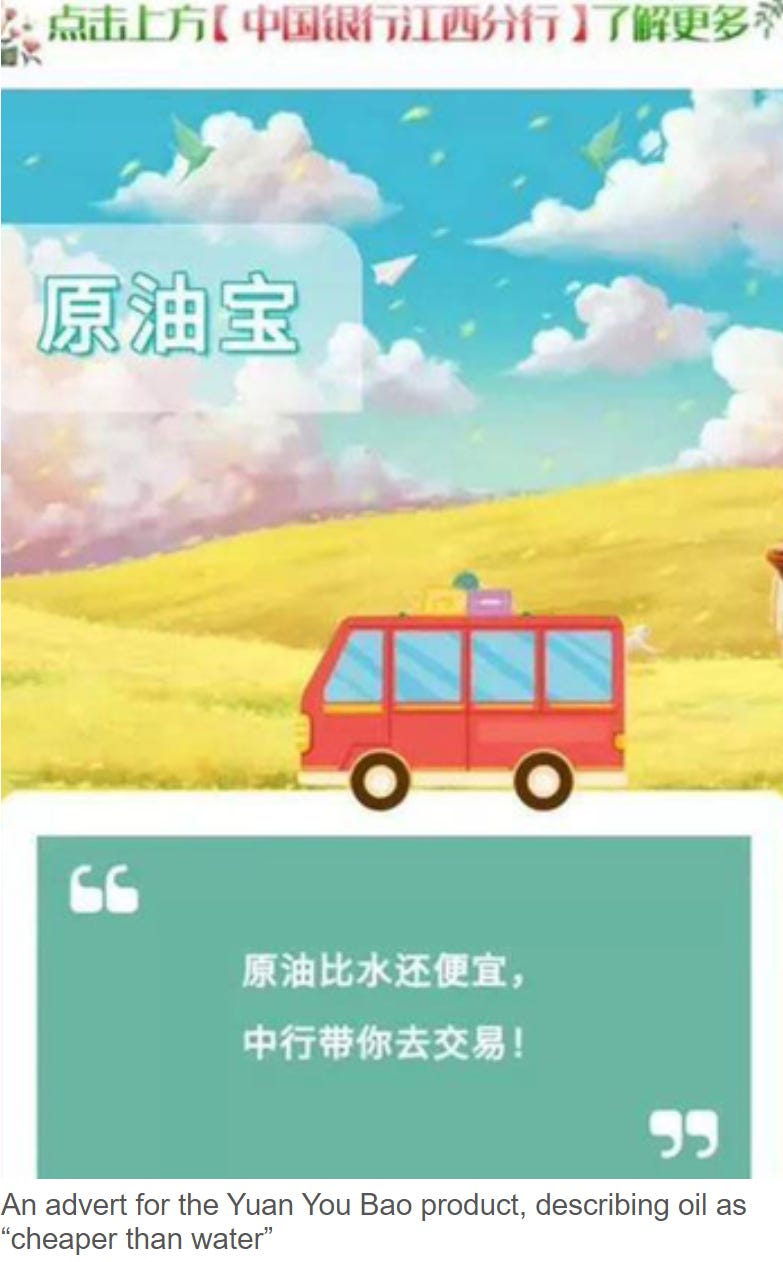

As I will return to in a moment, one major reason arbitrage did not happen was that it was not professional traders who realized those losses. As the CFTC reports, on April 20, the largest remaining long positions on the front month contracts were held not by commercial traders but by over-the-counter (OTC) swap dealers. In particular, the Bank of China (BoC) had a bulk of the outstanding positions in the May 2020 contracts on April 20, held on behalf of clients to which the Bank sold a custom financial product called Yuányóu Bǎo, or “Crude Oil Treasures”. Now, it is important to note that these “Crude Oil Treasures” did not allow for direct ownership of either oil or oil futures contracts; instead, they were swap contracts hedged with WTI futures. What the swap allowed for was exposure not to the price movement of crude (because they were used neither to buy nor sell physical crude) but to the ‘rollover yield’ realized from buying long-dated contracts and selling them as they neared expiration. This, it is important to note, reaps a positive return only when futures markets are in ‘backwardation’ (as, historically, oil futures markets usually are)—the situation opposite to contango—wherein front month contracts have higher prices than back months.

But, before I return to the very important role of the BoC, it is important to say that arbitrage also failed to occur for another two reasons. First, the $55 price swing down to -$40/bbl happened in less than a single trading day, with the largest portion of the squeeze happening in the final hour of trading. This is, of course, not a lot of time to arrange the transport and storage of tens or hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil—particularly with so few remaining open positions in the front month contracts. The price crash is in this way an example of the futures market failing to mediate the forwardness inherent to the oil trade.

But perhaps the most important reason why prices fell as far as they did, and in particular broke the $0 barrier, is because of the abrupt change to the rules governing the exchange for the remaining open positions. Once again, the bulk of open positions were linked to swaps. Like most over-the-counter contracts which use NYMEX as clearinghouse, the open interest linked to these outstanding positions is not placed on the intra-day trading order books. Rather, any asks for WTI futures linked to OTC contracts are posted on a different book for orders which settle at the closing price at the end of the trading day, or what is known as “traded-at-settlement” (TAS). The central issue on April 20 was that there was a very large amount of TAS ask orders which needed to be closed, given it was the day prior to expiry, but these positions could not find sufficient bidders in the TAS market. The price movement, in other words, was not the result of a ‘demand shock’ but a crisis of liquidity conditioned by certain specific mechanisms of the paper barrel trade. Realizing this threat early on April 20, NYMEX made the unprecedented move of telegraphing its participants and requiring any remaining front month futures holders to close their TAS position through the regular non-TAS order book by the last half-hour of the trading day.

As one might expect, this TAS mechanic was being actively exploited by professional day traders. In particular, a group of nine traders in Essex affiliated with a small UK-based trading firm called “Vega Capital” bought up many of the outstanding WTI contracts linked to swaps, including the Yuányóu Bǎo contracts, and then proceeded to short-sell WTI futures over the course of the trading day until they were “flat,” i.e. until all barrels bought off TAS were now matched by paper barrels sold on the regular market. This trading scheme was proven to be immensely successful as prices continued to fall over the course of the trading day, such that, at market close, the Essex group was able to profit off the difference between the OTC contracts they had already bought TAS and the futures they sold during the day. In fact, the crash into negative prices meant not only that they were profiting off the difference but were effectively being paid for the TAS contracts they had ‘bought’ at negative prices.

Much of the $660 million profit ultimately realized by the Essex group was derived from retail traders, in particular a group of roughly 60,000 small investment accounts holding the aforementioned Crude Oil Treasures. These participants were not professional traders but primarily middle- and low-income workers and students living both inside and outside of China. The latter had been sold these derivatives without being informed by the Bank of China of the possibility of negative prices, instead presuming them to be prudent “wealth management” products, as a Chinese college student described it. She had “invested” 70,000 yuan (approx. $10,000) into Crude Oil Treasures. After finally settling her position on her behalf on April 20, BoC promptly informed this college student that, as a result of her investment, she now owed the Bank 183,271.20 yuan (approx. $26,000).

Concluding Remarks

In sum, then, it was a combination of active exploitation of the trading day’s changing TAS rules, the selling of OTC derivatives to insufficiently informed retail traders, and, to be sure, some ongoing background macroeconomic events (e.g. the pandemic) which combined to precipitate the huge price drop on April 20. To reduce the dynamics underlying WTI’s price movement to a storage panic at Cushing is to miss entirely how the abrupt change to the mechanics of TAS trading, in a very clear and concrete way, conditioned this short-run price movement and in turn allowed for professional traders to capitalize off the slow response, misinformation, and general ineptitude of their retail counterparties.

More than that, overstating the effect of ‘supply and demand’ obfuscates the anarchic way in which the WTI futures market mediates the oil trade. It is commonly stated that the futures markets help ‘mitigate’ risk and therefore stabilize prices, but this is not really what any futures market ever does. What futures and other derivatives markets do is help some participants redistribute risk to other participants; and, increasingly in the oil market, this redistributed risk is absorbed by a new ‘counterparty of last resort’: the retail investor, who is providing liquidity—as is evident with the Yuányóu Bǎo, more liquidity than they even realize—in exchange for the false promise of passive ‘wealth generation.’

Of course, the liquidity provided by retail traders is a drop in the bucket compared to that provided by institutional investors, but I am not making the argument that it holds the entire trade afloat. Rather, my point is that it serves as an effective backstop for short-term panics. In effect, that is what retail financial products are designed to do. And, while BoC’s “Crude Oil Treasures” have since been scandalized and the Bank fined nearly $8 million by the CCP, this particular OTC swap contract is not some excessively speculative aberration of the normal procedures of the WTI futures market. It is one of a host of derivatives products explicitly marketed toward retail traders under misleading pretenses of gaining “exposure to oil prices”. I include here other analogous products offered by JP Morgan and the Royal Bank of Canada, as well as oil ETFs like the USO.

Explaining the effect of futures markets on short-term price shocks is the easy stuff, given how direct the links are between, e.g., TAS, retail traders, and the panic at Cushing. April 20, 2020 was a financial squeeze, pure and simple. Much more complex is the relationship between futures markets and long-term oil price movements. There, one must take more seriously a host of different macro-economic factors (including, to be sure, ex ante changes in supply and demand) as well as much more diffuse and indirect facets of the financialization of the oil industry over the past 30 years. But more on that another time.

For more on the physical delivery mechanisms underlying WTI futures, see: https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/WPM40-AnAnatomyoftheCrudeOilPricingSystem-BassamFattouh-2011.pdf

See more here: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2012/sep/pdf/bu-0912-8.pdf