Confidence about our progress toward Paris Agreement pledges rests on the reliability of data embodied in projections depicting what the world economy will look like 10, 20, 30 years into the future. Bloomberg, for instance, predicted in its New Energy Outlook 2022 that the astronomical growth in wind and solar farms seen in the 2010s would continue through the 2030s and, in turn, lead to effective replacement of coal and gas in heavy industry and power generation by 2050. Oil production, while admitted to be a more difficult predicament, is also supposed to taper off as its primary source of demand, transportation, is increasingly met by electric vehicles. Agreeing in its Global EV 2023 Outlook, the IEA anticipates under its “Stated Policies Scenario” (STEPS) that the share of EVs relative to total light-duty vehicles sold per annum will increase to 35% by 2030. In anticipation of this rapid scaling up of EVs, global oil demand is expected by the Agency to peak in that same year and, in turn, sink down to a steady ~100 million b/d by midcentury.

It should go without saying that economists and other market analysts are very bad at predicting the future, and especially the future of energy markets. Even in the immediate term, all of the above forecasts are dubious, if not wittingly fraudulent. As the IEA itself reported, wind and solar developers are already experiencing “financial headwinds” as a result of higher interest rates, pulling financiers away from less “bankable” projects. This cooling off of investment in renewables is especially pronounced in developing countries, where renewable buildout is already quite meager and where borrowing costs are two- or threefold higher than in the Global North. As for electric vehicles, consumer interest had already tapered off by the end of 2023 and new models have already become delayed or entirely canceled as the market sees the end of the ‘early adopter’ stage much sooner than anticipated. Once again, interest rates are a commonly cited source of blame for this setback. Finally, US oil is seeing yet another boom—and this one is actually profitable. In turn, the country is producing more oil than ever under the helm of the most climate-conscious president in its history.

Now, it would be one thing if analysts made these bullshit forecasts without much consequence, but most of these people retain very high degrees of influence among policymakers, becoming speakers at government-sponsored summits, consultants for things like the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, and authors of DOE-funded research reports. Hence, their impact in shaping discourse of mainstream climate politics is monumental.

It is precisely for this reason that poking holes in their projections ought to be a priority for anyone seriously committed to the end of fossil fuels. For, beyond keeping busy the otherwise soft, idle hands of wonks, these reports are intended to underwrite confidence in climate policies advertised to the public and, in turn, undermine any justification for more radical alternatives. There is no greater example of this than the brain trust of progressive liberals which converged during the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022. Shortly following news of is imminent success in the Senate, numerous research groups quickly released highly publicized assessment reports speculating on how the climate-related policies embedded in the IRA were putting the United States on a surefire energy transition pathway. The Center for American Progress touted the bill as putting the US on track to “reclaiming the mantle of global climate leadership.” Rhodium Group’s assessment hailed the bill as a “Turning Point for US Climate Progress.” Josh Bivens at the Economic Policy Institute wrote that, while “far from perfect,” the IRA “finally gave the the U.S. a real climate change policy.”

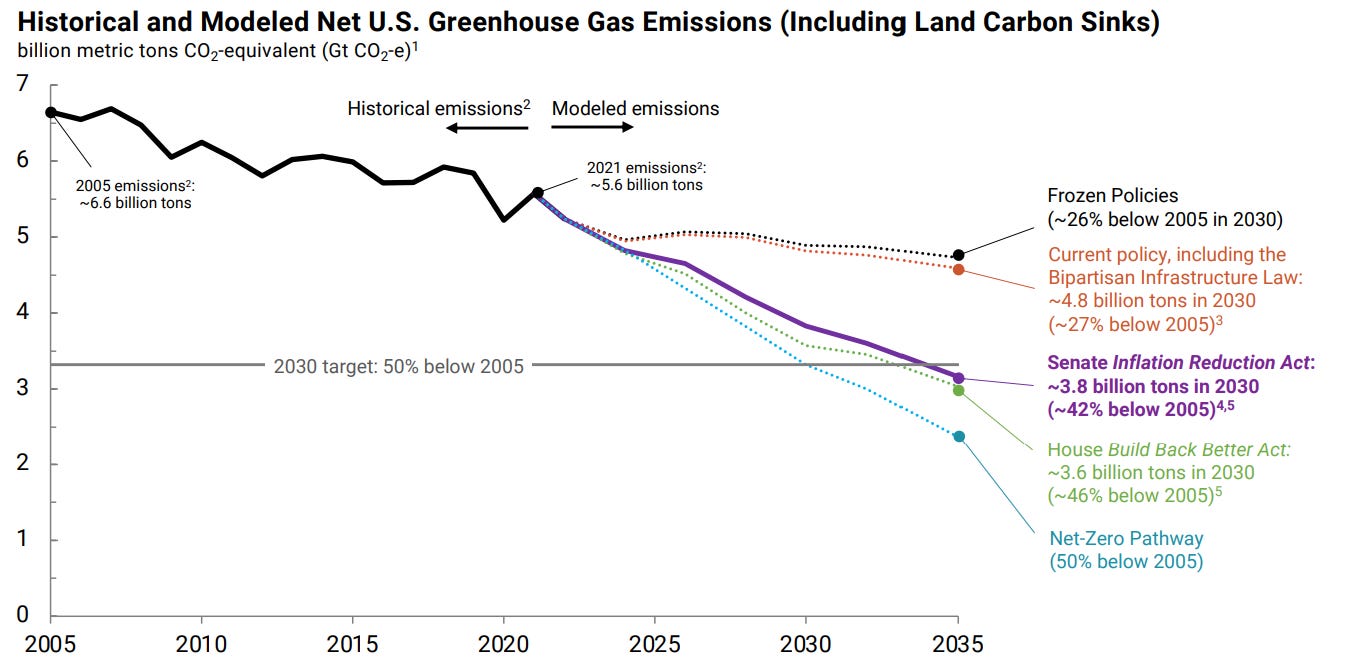

Perhaps most praised was the “Preliminary Report” of the REPEAT Project, a product of the crack team at Princeton University’s Zero Lab. Led by Jesse Jenkins, an assistant professor of engineering at Princeton, the Report came to the conclusion that the IRA bill had brought the United states to “within ~0.5 billion tons [of CO2-equivalent emissions per annum] of the 2030 climate target,” that is, to 50% of 2005 US emissions levels by 2030 (p. 6).

As provided in the Report, the above figure depicts the impact of the IRA bill in comparison with other economic scenarios, including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), signed into law by President Biden in November 2021, and the House-passed Build Back Better Act (BBA), which, while collapsing in the Senate after Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) broke away from majority support, became the basis of the renegotiated terms of the IRA. Considered against the “Frozen Policies” baseline, one can clearly see that, according to the Report, the IRA is expected to dramatically impact the downward slope of the country’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. In quantitative terms, it amounts to an annual emissions cut against the baseline of an additional ~1 billion metric tons of CO2-equivalent per annum.

To understand the tenuous nature of this projection—and, more importantly, its reliability as a proxy for decarbonization—it is worth pausing to reflect on the historical decline in emissions also depicted in the above graph. Why did this happen? Many will quickly point out the impact of the Obama administration’s much-touted fuel efficiency standards program. No doubt this was significant, at least early on, but it had an important and much less advertised side effect: footprint-based efficiency standards incentivized the manufacturing of more profitable, larger, gas-guzzling vehicles, such as trucks and SUVs, over lighter passenger cars. In addition to being a primary cause of rising pedestrian fatalities, this has also flattened the growth of gains in fuel efficiency.

The other significant source of decline in US emissions was, of course, the fracking boom. Infamously, President Obama had congratulated himself for this glowing achievement in the name of America’s ‘energy independence’. While the key effect of this with respect to emissions was the decommissioning of more carbon-intensive coal plants, it would be absurd to suggest that the 2010s downward slope will continue at the same rate for the next three decades. For, while relatively ‘cleaner’ than coal, gas-fueled plants still emit carbon dioxide and hence, still add fresh supplies of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. More than this, in fact, the proliferation of natural gas in the United States has led to extraordinary and largely unchecked pipeline and facility leakages of its predominant compound, methane, which is capable of trapping 28 times more heat than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period (and 80 times more heat over a 20-year period).

All of this is just to give you a sober, down-to-earth sense of the political economic conditions within which the IRA is being introduced, conditions which are completely ignored by such optimistic projections as outlined by Zero Lab’s Report. The idea that anybody could be confident about the bill’s facilitation of an energy transition is truly beyond my comprehension. There is nothing to be relieved about here, nor with the nominally ‘green’ economic pathway being blazed by the Biden administration.

And indeed, continuing on with Zero Lab’s Report, we see a slew of other slick charts accompanied with a basic line of naive economic reasoning, the gist of which goes something like: tax credits, rebates, and federal investments for renewables = cheaper, more efficient, and low-carbon electricity = less demand for fossil fuels = drawdown of greenhouse gas emissions. Thus, packaged in such projections is a nice, tidy story of the perfect mixture of market-friendly incentives gently guiding the US economy through its energy transition.

One year out, what do we see? In addition to the country producing more oil (and gas) than ever, the domestic LNG industry is absolutely booming, exporting an all-time monthly high of 8.6 million tons in December 2023. And although the IRA bill has certainly seen significant planned expansion for the country’s solar and wind capacity, a yearslong interconnection queue persists. While many blame this on regulatory overhead, the more fundamental economic issue is that the grid cannot handle the capacity being supplied by these new projects. In turn, when assessments demonstrate how expensive the cost of upgrading transmission lines will be, prospective generators end up pulling their applications. Beyond this, the country’s irrational private property regime requires organizing agreements across hundreds if not thousands of landowners for the construction of new high capacity lines. The bemoaned burden of environmental regulation is, in turn, largely a red herring: there is already plenty of overhead and lengthy, cumbersome negotiations going on in the ‘free market’ to slow down the energy transition.

Moreover, the above economic narrative proposed in the Zero Lab report is simply more bullshit. Brett Christophers’ new book has plainly revealed, the idea that markets move to the cheapest inputs presents a fundamental misunderstanding of the economic drivers of any supposed energy transition under capitalism. What matters is not cheapness but profitability. While there is no doubt that ‘green’ capitalists have been able to reduce costs of solar and wind energy over the past 20 years, this fact alone does not tell us anything about whether or not it is more profitable to do so. Under many circumstances, a switch to cheaper inputs is not, in fact, desirable on strictly economic grounds.

One of the key factors here, as Christophers explains, is that the cost profile of renewables steeply contrasts with that of conventional fossil fuels: while the former incurs most of their costs during construction—whereas costs of generation are virtually zero—the latter has its costs spread more evenly over the lifespan of its facilities. Hence, while conventional generators can price their output against the costs of inputs incurred during generation (fuel, labor), renewables price their output primarily against the (fixed) debts remaining to be serviced. This makes renewables much more vulnerable to increasingly volatile energy prices, as the static costs of renewables present a severe investment risk to renewable energy’s much-touted ‘green’ investors. Conversely, rates of profit are far more reliable with conventional generators because their primary input, fuel, remains a key driver of electricity prices. Hence, their costs adjust dynamically to fluctuating market conditions.

Added to this is the fact that the marketization of electricity generation has driven renewables costs down so low that independent producers have been racing each other to the bottom in European markets, skimming ever-thinning margins off of cratering prices during peak load times. In truth, the only thing stabilizing the revenues of renewable generators is government support, namely, in the form of feed-in tariffs, mandatory renewable energy purchasing, and purchasing power agreements. It should thus come as no surprise that, when the UK removed its renewables purchasing obligation scheme for onshore wind development in 2017, ‘green’ capitalists did not champion the good tidings of a more efficient electricity market. Rather, they left the sector: that same year, UK investments in green energy fell by 56%.

But I have saved the best of the bullshit energy transition projections for last: to make it to “net-zero,” the aforementioned “Preliminary Report” notoriously added additional emphasis on how the bill incentivizes carbon capture, namely through the “enhanced 45Q tax credit,” discussed in a previous post of mine. As the Report suggests, these tax credits purportedly make “carbon capture a viable economic option” (p. 13). This is despite a footnote on this same page quietly providing the caveat that “CO2 injection capacity in storage basins is likely to constrain the pace of carbon capture deployment.” This absolutely massive “constraint” apparently did not give the authors sufficient reason to challenge “expert input,” which suggested a possible “maximum annual CO2 injections increase to 200 Mt CO2/y by 2030,” or roughly 10 times current capacity. There is no current infrastructure (e.g. CO2 pipelines), let alone approved geological storage sites, which can handle this upscale in capacity.

Also left unmentioned in the Report is that the carbon captured through existing infrastructure is almost entirely used for enhanced oil recovery which, while touted as a means of lowering “carbon intensity,” does not attenuate but in fact exacerbates the problem of the net stock of carbon emissions in the atmosphere, which is what actually matters in assessing the impact of emissions on climate change. Unfortunately, the atmosphere will not reward us for more efficient exploitation of ecological collapse.

But in truth all of this gives far too much credit to the technical viability of utility-scale carbon capture than is actually deserved. Despite what some gullible socialists might have guilt-tripped you into believing, carbon capture is not a serious attempt to draw down the stock of carbon in the atmosphere. It is, on the one hand, a cash grab for venture capitalists and, on the other, a ruse for large carbon emitters to play with numbers in the aim of convincing regulators, stockholders, and the public that they have reduced carbon intensity of their internal operations. One only needs to check in with carbon credit markets, well-established now for decades, to get a sense of the trustworthiness of these accounting tricks. As The Guardian reported last month, more than 80% of rainforest carbon offset credits certified by Verra, the world’s largest carbon standard organization, are “worthless.”

It is maddening that we are even having to seriously entertain another round of these ridiculous schemes; and unconscionable that so many ‘socialists’ today are properly shilling for them. Truly, I see absolutely no reason to believe any of this. It is all premised on misunderstandings of the economic drivers for capital accumulation, the deleterious knock-on effects of organizing society around profit-making, and incredibly selective and disingenuous data farming.