Symbiosis and Conflict

Summarizing and commenting on Jean-Baptiste Fressoz's More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy (2024)

There has never been anything like an “energy transition” in all of human history, and there is no reason to believe we are currently on the precipice of one. This, at least, is the line Jean-Baptise Fressoz takes in his recent book, More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy (2024, English translation of Sans transition: Une nouvelle histoire de l'énergie). If you are familiar with this Substack or my Twitter account, you will know this is a thesis very near and dear to me (for example, here). And, no surprises, I am broadly in agreement with Fressoz’s book. The empirical points he raises are fairly straightforward: for instance, coal mining did not lead to the end of wood consumption but rather expanded its use-value, namely in pit props (Ch. 3); timber markets themselves dramatically expanded in terms of both finding new supply and demand thanks to the adoption of diesel-powered machinery and lorries (Ch. 4); and the ballooning of the oil industry in the early 20th century led to an even greater utilization of wood, as building its infrastructure required massive amounts of steel, which had to be forged in charcoal-burning (and coal-burning) blast furnaces (Ch. 5). Fressoz here manages to offer a great deal of insight simply be being scrupulous with the facts, outlining how an ever-growing, durable, and “symbiotic” matrix of material and energy flows subtends the global economy. And, as I will return to below, precisely this notion of “symbiosis”, otherwise vastly understated in both Marxist and liberal analyses of “green growth,” is the book’s most important contribution.

However, the argument has some significant weaknesses I would like to bring up here, primarily in order to draw some distance between his views and my own (in fact, what follows is probably as much of a self-critique as it is a critique of Fressoz). In particular, I want to touch on:

The matter-of-fact necessity of “symbiosis”

The limits of Fressoz’s critique of “technological progress”

Fressoz’s denouncement, very early on, of “political” histories of energy that leaves his own “all-consuming” one effectively subject-less

These three points are all closely related. Fressoz’s account of the objective necessity of symbiosis (and relative neglect of conflict) leads him to hypostatize “technological progress,” which, in turn, is what begets a subject-less history of energy. Now, to be clear, it is not that he does not identify specific people with ideological influence and decision-making power throughout the book, but what is opaque is the extent of their agency, i.e. their capacity to act otherwise, in producing this objective necessity that characterizes Fressoz’s “symbiosis.” It is for this reason that the argument ultimately relapses into a fatalism within which “humanity” is indicted for producing this catastrophic, ecocidal force called “technological progress.” False consciousness—transition, this spurious projection of a “past that does not exist onto an elusive future” (p. 2)—is replaced with an unhappy one, the deliverance from which demands absolution—a “voluntary” and “enormous energy amputation,” as he describes it (p. 13).

This conclusion is not unfamiliar. It evokes a technological pessimism with a long, contentious history in the humanities. And, to be clear, I am not entirely unsympathetic to this line of thought. Of course, one must acknowledge its innumerable critiques, most prominently in recent years in the repudiation of the specter/scapegoat/bogeyman of the Anthropocene and its same abstract indictment of “the human,” qua Anthropos, for ecological collapse. But there is a cliche that runs unchallenged in this literature—to gloss too quickly, the cliche of difference and/or contingency as ontological safeguards for all past, present, and future socioecological transformation—and, here, I believe Fressoz is right to insist we must face the immense inertia of the world as it really is: cumbersome, complex, thoroughly interdependent, and, most alarmingly, supported by an insatiable, ever-increasing throughput of huge stocks of material and energy. Despite the tumultuousness of climate change, then, what Fressoz correctly notes is how much of the capitalist world system and its material infrastructure are in fact profoundly unchanging.

So, if Fressoz’s book has been particularly generative for me, it is because it raises to the surface what I take to be the fundamental dilemma of climate politics: how do we account for the real stakes of the “climate imperative” without being defeated by its, truly, “all-consuming” nature? I fully agree with Fressoz that “energy transition” fails spectacularly to resolve this dilemma. But, it must be said, Fressoz has no positive answer himself, and he seems to only mock the attempt at one. At the end of his book, he departs us with a scoff: there is “no magic bullet, no ‘real transition’ programme, no emancipating green utopia” to offer (p. 220). A cheap, trite excuse for not engaging with the problem of subject formation that haunts the entire book, and which in turn risks blunting his otherwise very sharp critique.

To emphasize: the book’s premise is, to my mind, irrefutable (as much better put in the French title, Sans transition), and Fressoz is correct to suggest that we often are not dealing with the problem at the scale and scope it demands to be dealt with. What I take issue with is his method of investigation and how it shapes his resulting fatalistic, “all-consuming” history. The latter is just as untenable as “energy transition,” empirically, politically, and ethically. This is all the more ironic given the book emphasis on “material history”; yet, what is presented is precisely the kind of “materialism” that Marx and Engels had derided as “contemplative,” wherein the object of analysis, the history of energy, remains unmediated, matter-of-fact: never grasped subjectively, as a practical activity, a real archive of social struggle, but only one-sidedly, as merely objective necessity. Correction would mean, among other things, returning to this material history its “ideal form” in Evald Ilyenkov’s sense—or, precisely what Fressoz rebukes at the outset as the “political history” of energy.

An All-Consuming Symbiosis

At the outset, Fressoz notes ample evidence that ought to make his thesis self-evident:

Despite significant growth in renewable energy, the global economy has never burned as much oil and gas as it does today (p. 2).

Three times more wood fuel is burned today than a century ago, thus refuting the presumption that it had been replaced by coal during the Industrial Revolution (p. 2).

95% of coal that has ever been burned has been burned after 1900. The strongest growth in coal consumption in fact occurred from 1980-2010, after the supposed “Coal Age” (p. 3).

The supposed “decoupling” of GDP growth in Western Europe from carbon emissions is a statistical artifact of offshoring heavy production, and thus the re-allocation of emissions to producing countries rather than consuming ones (p. 4).

Even more, to the extent that e.g. Switzerland still profits greatly off of housing the headquarters off of global commodity trading companies like Glencore, “decoupling” is a financial mystification more than it is an accurate representation of Europe’s fossil fuel dependency (p. 5).

But what is more difficult to understand is the misalignment between, on the one hand, this preponderance of evidence that no energy transition has ever occurred or is currently in the works and, on the other, the hailing of an imminent “energy transition” by politicians, academics, and even many climate activists. The impropriety of this concept for our current conjuncture is what, in turn, occasions Fressoz’s writing, both to substantiate the historical absence of any “energy transition” over the past 250 years, as well as to conduct an ideology critique to explain why these “obvious” facts have received such scarce acknowledgment.

The first aspect—let us call it the empirico-historical argument—comprises a majority of the text, taking the form of historical reconstruction of the complex, “symbiotic” relationships that have unfolded across economies of wood, coal, and oil. But it is, in my view, this latter aspect—the ideology critique—which more clearly reveals the limits of the prior historiographical study. Thus it is worth recapitulating Fressoz’s ideology critique rather extensively.

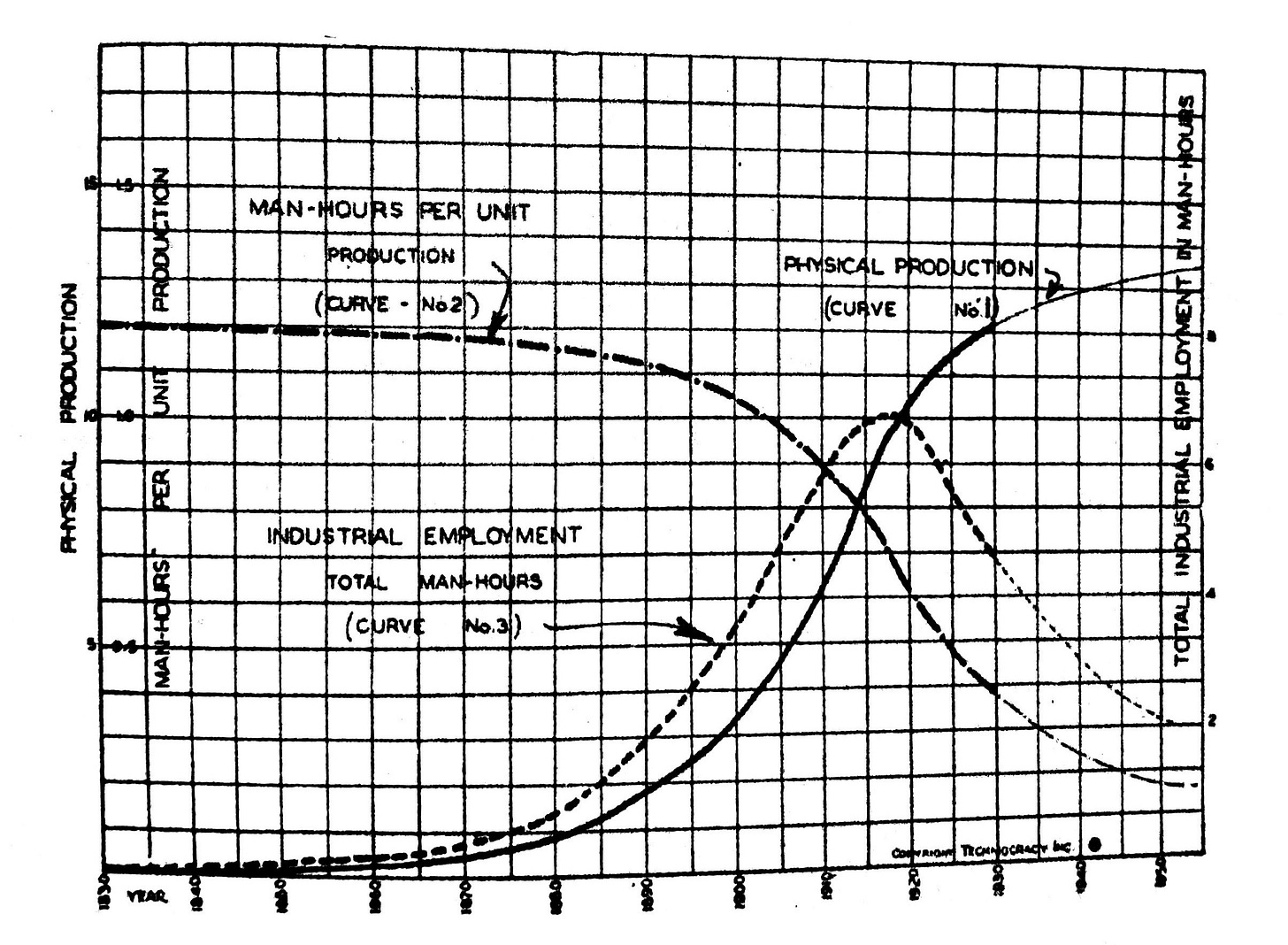

Primarily covered in the last third of the book, what Fressoz presents there is a comparative discursive analysis of “energy” as it has mutated across different social contexts. Specifically, he locates the germ of “energy transition” not in the 1970s energy crisis, as has been commonly identified, but four decades prior in the US-based Technocracy Movement. Here, what Fressoz finds significant is the early technocrats’ assessment of the Great Depression as not merely a cyclical economic downturn but something far more chronic and, indeed, fatal. In brief, the technocrats argued that at the root of the crisis was the problem of electrification, which had in turn allowed for the technological substitution of labor, which reduced demand for consumer goods, which forced capitalists to reduce prices, which incentivized further technological substitution, ad infinitum. What this untimely concurrence of mass employment with energy abundance thus revealed was the looming obsolescence of an economy based on the scarcity of labor:

It was physically impossible to reduce unemployment because labour productivity was such that full employment would require staggering quantities of raw materials and energy. The crisis of 1929 was therefore neither financial nor economic: instead, it was both technological and Malthusian, corresponding with the peak of an ultra-productive economy in a finite world. (p. 137)

To further rationalize the necessity of socioeconomic transformation, the technocrats relied heavily upon the predictive power of the “S-curve”, as popularized by Raymond Pearl, a biologist who had inferred it to be regulating the population dynamics of the drosophila flies he was studying. In brief, the S-curve promoted the idea that population growth is not additive but exponential, as Thomas Malthus had argued a century prior, and will flatten only once it exhausts its ultimate, finite possibility, e.g., in food supply. Inspired by this idea, technocratic luminaries like M. King Hubbert began to apply the S-curve to all sorts of social and economic variables. Beyond population growth, rates of consumption of finite resources like coal in particular became subject to the “iron law of the logistic function” (p. 176).

Here is thus where the kernel of “energy transition” first emerges, namely, as a conclusion reached by 1930s technocrats who were applying the S-curve to the rational management of the economy—or perhaps better put, the economic management of society. While the S-curve of this or that variable was deemed unimpeachable, what the technocrats nevertheless also insisted was that individual S-curves could be replaced through the force of “innovation.” Here, of course, they relied heavily on the work of Joseph Schumpeter to demonstrate this possibility of staving off the cataclysmic effects of the stagnant right tail of the S-curve through the continuous “creative destruction” inherent to technological progress.

And indeed, the solution to the 1970s energy crisis and its concomitant ‘stagflation’ came to be interpreted in much the same manner, where historical energy transitions were modeled as a series of successive S-curves (wood → coal, coal → oil), and in turn the question of a future transition concerned replacing the oil S-curve with a new energy source. By far the loudest advocates for this model of “energy transition” were nuclear energy lobbyists, who had been warning of the inevitable depletion of fossil fuels—and, what’s more, the climatological effects of their associated emissions—since the 1950s. But, as Fressoz notes, even those wary of the “atomic technocracy” demanded by nuclear energy, i.e. the necessarily centralized and hierarchical management of its production, likewise adopted the S-curve paradigm. By the 1970s, major environmental organizations like the Sierra Club and the Friends of the Earth began to promote a “solar transition” which, while ostensibly embodying more democratic principles, was nevertheless premised on technological diffusionism, rather than any direct confrontation with the underlying organization of society. And, as Fressoz goes on to show, this technocratic futurology is indeed what informs the “energy transition” of the contemporary period—despite its markedly different context, constraints, and objectives—finding its way all the way to Group III of the IPCC, for whom the diffusion of increasingly exotic negative emissions technology has become essential to addressing global carbon emissions.

But “energy transition” has not simply remained the pet project of technocrats and uncritical climate scientists; for Fressoz, it has been thoroughly redressed in the “lexicon of sociological theories” (p. 12). Bruno Latour is, as one might expect, a central target here: insofar as he praises innovators like Louis Pasteur as being capable of “completely [reconfiguring] society,” Latour inherits this ideological convergence of the Malthusian S-curve with Schumpeterian “creative destruction.” Beyond Latour, however, Fressoz suggests more provocatively that this widespread fixation on the contingent and improvisational aspects of technoscience, a hallmark of social constructionism, has done “little to help us understand the nature of the climate challenge, which is characterized, on the contrary, by a high degree of certainty and is caused by the terrible inflexibility of old techniques” (p. 178).

Here is thus where we can see Fressoz’s notion of “symbiosis” plays its most polemical role. Not only, in other words, is it provided as a means of critiquing the Marxist and liberal emphases on competition as ultimate driver of capitalist development. Simultaneously, “symbiosis” is provided as antidote to the poststructuralist affinity for contingency, uncertainty, and flux, which, for Fressoz, had obfuscated, wittingly or unwittingly, the profound inertia of our global energy infrastructure.

While I find this critique compelling on its face, the problem, once again, is with how Fressoz historically reconstructs the “necessity” of these symbiotic relationships earlier in the book. Keeping the above ideology critique in mind, let us thus now turn to his prior discussion of wood fuel: against the common presumption that coal mines in Great Britain replaced wood as a source of energy, Fressoz notes that wood consumption within the energy industry actually increased in the country over the course of the 19th century. Hidden in the commonly cited statistics of wood fuel vs. coal consumption is the fact that wood became an indispensable material for coal mining, namely, in the construction of pit props. The invention of a new use-value for wood, beyond its use as fuel, thus led to a voracious new source of demand, such that Great Britain would end up consuming six to seven times more woodland “to produce energy in 1900 as it had a century and a half earlier” (p. 46).

And, as Fressoz will note later on in the text, even this should not lead the reader to believe that this old use-value for wood as fuel has disappeared, for at the global scale charcoal is used to produce more metallurgical heat now than ever (p. 59). Fressoz offers a powerful example: the French company Vallourec, one of the largest charcoal producers in the world, “probably” harvests more wood in a single year (~3 million cubic meters) than the “consumption of the world oil industry at the end of the nineteenth century, when derricks, barrels and tanks were all made of wood” (p. 100). Even more: while open-pit mines may have “broken free” from the dependency of coal production on wood, their deployment of diesel-powered machinery has only guaranteed their consumption of huge amounts of refined petroleum products, themselves reliant upon oilfield infrastructure made of steel, which is, once again, forged in coal- and charcoal-burning blast furnaces around the world (p. 55).

These historical observations of the interlinking interdependencies of energy and material flows are what give flesh to Fressoz’s concept of symbiosis. But these ‘facts’ are taken entirely one-sidedly, such that they can cleanly prefigure his subsequent critique of “technological progress,” as noted above. This cannot help but lead Fressoz to exasperation by the end of the book—noting how there are as many elements within a tire in 2020 as a whole car contained a century earlier, he muses:

By increasing the material complexity of objects, technological progress reinforces the symbiotic nature of the economy […] Over time, the material world has become an increasingly vast and complex matrix, entangling a greater variety of materials, each consumed in greater quantities. These few historical observations do not derive from an irrefutable law of thermodynamics: they merely illustrate the enormity of the challenge ahead—or the scale of the disaster to come. (p. 218)

Here, it is as if he indeed senses the impending critique (“these few historical observations do not derive from an irrefutable law of thermodynamics”) and thus intends to leave the possibility of transformation is open, perhaps—but for who, and by what means? Answers are absent, for the book builds toward a “symbiosis” that is “all-consuming,” its output a “material complexity of objects” that is not just daunting but insurmountable, save for the aforementioned “energy amputation” that would be, let us be honest with ourselves, just as apocalyptic as the harrowing visions of the right tail of an S-curve promoted by the 1930s technocrats. Cocooned in this “symbiosis” he has reconstructed in the history of energy, Fressoz can only mock the “nebulous group of neo-Keynesian experts, the NGOs and foundations thriving in the shadow of COPs” who idly assess the “cost of transition […] without any indication of how this fortune would change the chemistry of cement, steel or nitrogen oxides, or how it would convince producing countries to close their oil and gas wells” (p. 219).

But where is Fressoz’s indication? This is not to my mind a question of providing “magic bullets,” as Fressoz glibly retorts. It is fundamentally a question of being able to articulate “objective necessity” not simply in terms of “technological progress” but as the very shape of social struggle, as the necessary content of this “all-consuming” “symbiosis” of material and energy.

The Matter of Facts

In Endnotes’ essay “Error,” a point very similar to Fressoz’s trepidation about tires is raised: “What are we to make of the micro-component that is useless in abstraction from elaborate global supply-chains, such as, for example, the old iMac’s 922-9884 Screw, T10, WH, DLTA, PT3X24MM?” (p. 146). Commodity production is thus recognized by the authors not only as implying a profoundly “complex materiality” but also as signaling how little utility there is in any given individual component outside of the capitalist relationships it presupposes. So much of the “material world” is, in other words, designed and made for purposes (i.e., profit-making) at odds with a de-commodified life shared in common. Technology is thus here plainly recognized to be not some neutral substrate, easily adaptable toward new ends, but, echoing Fressoz, already determining our capacities and limits of action in the world. Though the example of the iMac screw is trivial, in this way the authors’ concern extends to a more general dilemma for communist politics: what is being appropriated when, in their struggle against the existing state of things, the proletariat turns to appropriate the “productive forces” of capitalist society (displacing for a moment the crucial distinction between technology and productive forces)?

For the authors of Endnotes, this is a difficult problem, but it is not an unanswerable one. First, they write, accepting that the capitalist world does indeed provision the parameters of our “action and behavior” does not necessitate conceding the impetus of the struggle against the former to an “ineffable negativity” (p. 117; on this point see an analogous critique I make of Wainwright and Mann’s Climate Leviathan). It is precisely the task of the critical theorist not to resign oneself to the cold matter of facts but to find their transcendence already given in the “shape of the world as it is” (p. 135). With this in mind, we can re-read Fressoz’s insistence on addressing the climate crisis at the scale it deserves by saying that it, indeed, has already made this demand of us: it is already determining our subjectivity at the scale of the planetary, and what is at stake for the theorist is articulating the shape this subjectivity not only must take but is already taking.

But this is also to say that the “shape of the world” is not and cannot be homologous with this smoothly “symbiotic” space of capitalist development as envisioned by Fressoz. For one, there are countless vulnerabilities that present themselves as local opportunities for struggle and thus the rejuvenation of class antagonism: pipelines, ports, terminals, all sorts of of chokepoints that can be and are leveraged in the struggle against capital. Here, citing the work of Timothy Mitchell and Andreas Malm (and indeed just those two), Fressoz insists that the best attempts to “inject politics” into the “economic history of energy” have merely repeated the “standard transitionist story” (p. 7). In turn, the only sustained engagement Fressoz makes with the history of labor throughout the book is in Chapter 6, but only in order to refute Mitchell’s Carbon Democracy—not for its oft-criticized ‘technological determinism’ but for failing to take into account the fact that oil never replaced coal and, hence, Mitchell missed the “energy coordination” that powers our global technological infrastructure. In contrast to this, however, the irreducibly “political” task of writing a materialist history of energy would entail connecting past and present struggles into a broader image of resistance, one which has already been at work negating the “transistionist narrative” Fressoz rightly critiques. More generally, it would entail grounding the very possibility of “symbiosis” in the presence and indeed persistence of countless divisions already sewn into the supply chains of the global economy.

In this way, neither “energy transition” nor “energy amputation” but the possibility of socioecological transformation is to be recognized as immanent to the world as it already is—albeit a “future” often, and necessarily, only speculatively retrieved. This is precisely what the Endnotes authors mean by “error” in the engineering sense of the term, as the “objective gulf between the unavoidable abstractions of the revolutionary imaginary and the real conditions of any actual revolution” (p. 159). Already given in the world is not merely the interlocking interdependencies of the “symbiotic nature of the economy,” as Fressoz has it, but also the “negative specification of the space of affordances in which particular ends may be pursued” (p. 160).

David Noble had recognized how, in its “very concreteness, people tend to confront technology as an irreducible brute fact, a given, a first cause, rather than as hardened history, frozen fragments of human and social endeavor” (2011, p. xiii). In his one-sided promotion of the notion of symbiosis, Fressoz’s history of energy continuously risks the same positivistic assessment of the “complex materiality of objects.” Renouncing previous attempts at the “injection of politics” into the history of energy, Fressoz’s own reconstruction remains, at best, half-finished. Its real completion could not hold such a one-sided, flattening “symbiosis” as telos of an irreducibly social history so riven with conflict; or, better put, it is precisely the telos of labor that is missing from Fressoz’s narrative of all-consuming symbiosis.