The Early American Oil Markets (Part 2)

The petroleum exchanges and the problem of periodizing financialization

The Introduction of Oil Pipelines and the First Petroleum Exchanges

Pipelines helped greatly to insulate the transportation of oil against environmental hazards. When they were first introduced in 1865, one of the most important consequences for the oil trade was the coincident introduction of sturdy cast iron storage tanks, likewise designed to withstand the vagaries of the weather. Their advantage, however, was double-edged: while standardization allowed oil going into the tanks to be much more easily measurable than before, once the oil went inside, it “lost its identity by absorption into the general stocks” (Boyle, 1915, p. 8). Relief from the “bickerings” over an “honest barrel” was thus exchanged for a new problem of the anonymity of oil after its purchase.

Being already off the books and in circulation as far as producers were concerned, this anonymity led to new risks for pipeline companies, who found it difficult to enforce storage or pipeage fees, to say nothing of the removal of idle unsold oil back to its original producers. Unwittingly, the pipelines became a physical hedge for producers, as it was now the line companies that took on the risk of holding oil until it could be sold to a shipper, who then had to be trusted to pay the bills. Desiring to return this risk back to the producers, line companies quickly introduced a new contractual arrangement between themselves and producers where, instead of paying for oil in cash at the storage tank, pipers issued producers “pipeline certificates.” These certificates required routine verification at the office of the pipeline company for payment of storage charges, regardless of who the current holder of the certificate was, else they could be voided. This, in turn, not only offset the risk back to producers but obligated the latter to become more proactive in finding a shipper, as the pipeline company could now refuse to honor the certificate until fees were paid.1

“The system was simple; when producers placed oil in a pipeline, they were said to have a ‘credit balance’ in the pipeline company’s books, and could receive certificates in denomination equal to their balance” (Weiner, 2003, p. 5). By the late 1860s, three different types of certificates had already been standardized, quite reminiscent of modern futures exchanges: “spot” contracts for same-day delivery; “regular” contracts for delivery within a 10-day window of issuance; and “futures” contracts with monthly expiries. As stated above, a charge was typically also incurred for this service, payable in oil, which covered leaks, evaporation, and other risks associated with storage. Conversely, while the pipeline company never held title to the oil, the certificate system rendered them liable for on-demand delivery at request of the buyer; hence, this compelled the pipeline companies to always keep in storage an “amount of merchantable crude petroleum, equal to its credit balances” (Bell, 1890, p. 510).

The “high-class” creditworthiness of pipeline companies—especially once all of the pipelines in Pennsylvanian oil country had been consolidated under United Pipe Lines, a Standard Oil company, in the 1870s2—made these certificates as ‘good as gold’ in serving as a medium for the circulation of value. Thus, functioning “similar in all respects, to a deposit in a bank” (ibid., p. 510), it quickly became possible to use the certificates not merely as a representation of the value of the underlying oil commodity but as a bona fide and fungible financial product.

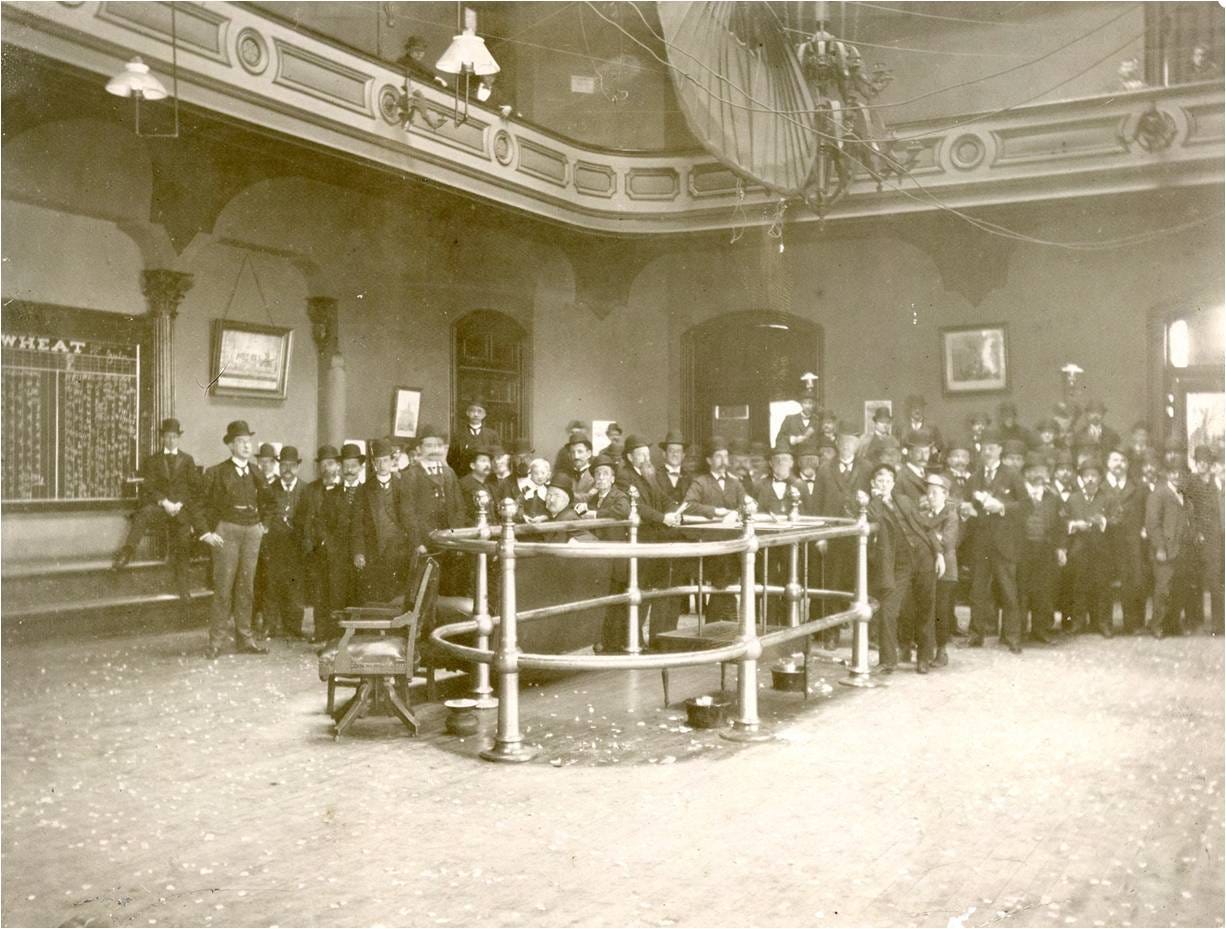

At the same time, rather than find a buyer directly, producers began to sell their certificates for cash to those willing to take on the risk of future price changes (Brown and Partridge, 1998, p. 571). This motivation, in turn, became the real basis for the financialization of oil in the early days of the industry. Formal exchanges quickly emerged for the trading of pipeline certificates, first in Titusville in January 1871, then Oil City shortly after (albeit both were abruptly closed for reason of lack of trading volume and reorganized in the coming years), and then across numerous major American cities, with Cleveland, Chicago, Cincinnati, New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh at one point or another all having petroleum exchanges.

Robert Weiner provides a concise description of how trading became formalized during this period:

The exchanges had formal rules similar in many ways to those of today. Conferences of exchanges were held to standardize these rules, to negotiate with the pipeline companies, and to verify their assets. Self-regulation was enforced by inter alia, maintaining an arbitration committee and limiting membership. Members were forbidden to trade outside of the exchanges (known as “curbsome trading”), and could be fined by the exchange for doing so. Such trading flourished, however, often outside of exchange hours […] (2003, p. 11).

The proliferation of information was a crucial means by which exchanges sought to regulate prices. The use of private wires set up between trading houses, for instance, enabled inter-exchange arbitrage (Barbour, 1928, p. 131). Brokers would also post Bulletin Boards in front of their offices with prices updated every half hour during the trading day (10 AM to 12 PM and 1PM to 4PM Monday through Friday, except holidays). In the effort to preempt reckless speculation, the early exchanges limited membership, primarily to elite men of known business stature, and slowed down trading through the charging of high commission fees (ibid., pp. 130-131).

New Ways to Speculate

However, despite these information control and anti-speculation measures, market manipulation was rampant. In 1869, even before formal exchanges emerged, a “ring” had purportedly bought up enough futures for later in the year that they constructed a successful and lucrative corner on the market (Weiner, 2003, p. 7). As the exchanges emerged, more sophisticated “syndicates” began to form. There was, for instance, the “Penn Bank Syndicate,” organized in 1883, which conspired to raise the price of oil to $1.50 per barrel by manufacturing buying pressure between members in tandem with the public release of reports of favorable market conditions (Barbour, 1928, p. 138). Once trading momentum swelled to pull a sufficient mass of smaller traders into the corner, the Syndicate planned to then pull the rug and dump its positions.

Notably, however, Standard Oil stood strongly against the price raise. Having caught wind of this collusion, Standard simply withdrew its deposits from the participating banks. Being one of their central depositors, this all but forced the dissolution of the Syndicate. More generally, speculation became increasingly pronounced as competition between exchanges compelled them to lower barriers to entry, particularly by reducing brokerage fees.

Although producers themselves often used the exchanges to speculate, they also actively organized against the effect of exchanges on oil prices. The Petroleum Producers’ Union, for instance, formed in 1878 with the aim of combatting the low prices which they claimed were caused, in part, by the “manipulation of the stocks by speculators and buyers to depress price to suit their purposes” (qtd. in Weiner, 2003, p. 20, note 54). Such producers’ cartels were hard to maintain, however. Tasked with voluntary output restraints, members frequently “succumbed to the temptation to cheat as hordes of new drillers, eager to strike it rich, continued discovering new gushers” (McNally, 2017, pp. 18-19).

Thus, efforts among producers to rein in the pricing power of the markets ultimately failed. By 1874, the oil exchange was already “accepted at home and abroad as a price-making factor to the exclusion of economic principles of supply and demand” (Boyle, 1915, p. 9). Even further, by the 1880s the total flow of oil through pipelines superseded railroad transportation, precisely as margin trading on the exchanges had superseded cash “almost entirely” (Tennent, 1915, p. 13). This, in turn, meant volume on the exchange greatly increased over the decade and, with the loosening of commission fees and the proliferation of brokers, included a new class of traders, the public, which now fueled speculation not only indirectly through oil company stocks (as mentioned in Part 1) but in a much more direct way through the futures trade. “If a person sat down to have his shoes blackened, the bootblack was either a bull or a bear and in some way speculating in oil. He would tell of the different things that he had heard on his side. The dining room girls, the clerks, the cashier, the president of the bank, everyone would be speculating” (ibid., 1915, p. 14). It seemed “as if every fellow who could raise $100 or more was in the market” (Barbour, 1928, p. 133). As August Giebelhaus (1977) notes, even Joseph Pew, founder of Sun Oil, had purportedly been caught up in the paper trade as a young oil man, losing thousands of dollars while speculating on pipeline certificates (pp. 26-27).

That said, the public were mere “lambs for the slaughter” when pitted against the wolves of the market, i.e. professional traders (Boyle, 1915, p. 9). There are two main reasons for the structural vulnerability of the former to the latter. For one, professional speculators had much larger pools of funds with which to influence the paper trade, particularly when they were part of larger syndicates. More capital allowed them to draw smaller hands into the momentum of swing trading essentially at their discretion. Secondly, the ‘price indicators’ for speculators had less to do with earnest assessments of the “general situation” than with the construction of “rumor factories […] to fool the public” (Boyle, 1915, p. 9). As is common to other exchanges (then and now), these rumor factories were split between two departments, one for the “bulls” and the other for the “bears.” Whereas the former wanted the price of oil to rise, the latter wanted it to fall. To realize these price movements, the bulls and bears became masters of financial ill-advisement: the bears attempted to convince other market participants that oil production rates had skyrocketed; in reply, the bulls argued that, e.g., Standard Oil’s purchases were clear indications of favorable market conditions. But rumors went well beyond general market analyses: speculators would also promote at best unsubstantiated and at worse deliberately false claims about recent, highly watched wells having been proven to be dry holes or gushers. And such hearsay did not only involve events in the oil patch but national news items as well: the assassination of President James Garfield in 1881, for instance, was interpreted by traders to have an imminent, destabilizing effect on the oil trade. Prices subsequently rose, despite millions of barrels of oil already in excess capacity accrued that year (Barbour, 1928, p. 134).

While producers were at risk of getting caught underneath the rumor mill and realizing low or non-existing rates of profit, contestation of misinformation was often not worth sacrificing details about their actual oilfield successes and failures. Indeed sometimes they used this insider information to take advantage of exchange prices when they believed them to be above or below oil’s real value: “The size of discoveries [was] often concealed by producers (referred to as ‘mystifying’ or ‘making a mystery of’ a well), in order to take advantage of superior information by buying or selling on the exchanges” (Weiner, 2003, pp. 21-22; see also Brown and Partridge, 1998, p. 572).

The Scouts

In response to this concealment of production information, and with the futures exchange an unreliable indicator of market conditions, shippers hired scouts to gather intelligence in the oil patch. These “Night Riders” developed an array of tactics to subvert the secrecy of producers, who often employed armed guards to establish perimeters around their prospects.

A former scout, James Tennent, recalls his first appointment in the Cherry Grove field, where he gathered information about the depth of a “mystery” well by measuring with a level the height of the hill upon which it sat and comparing it to the known depth of a well lower in the valley (sometime later, he procured an aneroid from John Franklin Carll, a Pennsylvanian state geologist, which would allow him to do the same much more quickly and covertly). To better observe drilling activity, he also exploited the surrounding physical geography, hiding “under a shelving rock” situated on a higher hillside “where I could look down and had a good view of what they were doing” (Tennent, 1915, p. 17).

Scouts would also gather intelligence around town, eavesdropping on oil men, intercepting telegraph messages, or simply talking with townsfolk who were likely to have heard a thing or two about recent oil discoveries. Being acquainted with contractors also helped: tank builders, for instance, often worked close to the wellhead and hence passively gathered information from operators about flow rates, drilling depth, and so on. Tennent recalls one time paying a tank builder $5 to procure a sample of oil from a mystery well in order to compare it to known samples of other nearby fields (ibid., p. 22). If they managed direct observation of the well, scouts could make even more refined assessments of drilling activity: drill depth, for example, could be inferred by watching the resetting of tools at the wellhead and knowing the length of the grits of the derrick against which the drill cable passed. To know whether drilling had proved successful, scouts would observe the gas which accompanied oil as it escaped out of nearby vents and varied with changes to the flow and volume of oil. Sometimes, they could even make it directly to the well, either because it was abandoned as a dry hole or because the armed guards loosened their defenses, particularly at night—for instance, by casually watching the field while “in a shanty playing cards” (ibid., p. 19). Access to the well allowed for direct verification of their field observations, e.g. of well depth, and also more reliable measurements of flow and pressure, viz. by listening to the pipes feeding into the tank house.

Despite the purportedly noble service they provided to the oil trade, tasked with keeping all of its participants honest, scouts themselves apparently had few qualms about profiting off of the privileged information they procured. Indeed, realizing the value they provided, brokers and speculators “were willing to handle oil for them without margins or charging any commission” (ibid., p. 43; see also pp. 57-61). Insider trading was not particularly stigmatized among scouts, who thus not only disseminated production information but at times actively obstructed it. Indeed, they objected to open information about oil wells precisely because they “wanted a mystery. That was their business—to solve the mysteries, for where the information was free and open to everybody they could get but little advantage over the public” (ibid., p. 45).

Tennent recounts a notable instance where, in exchange for handling 25,000 barrels of produced oil, he and a few other scouts colluded with a drilling contractor to delay drilling for a prospect which was expected by many traders to yield a gusher. To make a convincing case for the delay, the driller deliberately sabotaged his own equipment and sent it to the tool dresser for repair. At night, after the other scouts had departed, Tennent and his team commenced drilling with the contractor and discovered that the well was dry. This, Tennent reckoned, would “create a panic on the Exchanges when it became generally known, for the reason that there had been so much short oil sold on the strength of this well being a gusher” (ibid., p. 46). As the team had journeyed back to the exchange in the morning, they crossed paths with friendly scouts headed out to the well. They managed to convince some of them to turn around in exchange for “some information regarding the well, provided they allowed [Tennent and his team] 20 minutes time after the opening of the Exchanges.” At market open, Tennent promptly bought 25,000 barrels of oil, releasing information about the dry well half an hour later. To further reward those scouts who turned around, they arranged with the drilling contractor to not commence drilling until an hour into the trading day. “This was one of the best scoops the scouts ever made” (ibid., p. 47).

Standard Oil Ends the Petroleum Exchanges

While Rockefeller would have preferred stable prices, Standard Oil tolerated the wild speculation of the petroleum exchanges insofar as the company could always adjust its storage costs in order to insulate it from price swings. In 1887, however, a bill was introduced by James K. Billingsly in the Pennsylvania State Legislature to regulate the charges pipelines made for storage and transportation of oil “at the demand of the holder” (Barbour, 1928, p. 142). Although the bill never passed, the associated scrutiny lawmakers placed on the oil trade put pressure on Standard Oil, now the sole owner of all of the state’s pipelines, to come to a compromise with regional producers, who had long been protesting the variable fees associated with storage. Eventually, Standard Oil agreed to a fixed reduction of storage charges from $0.4123 to $0.25 a day, per 1000 barrels.

However, being therefore less able to adjust costs, Standard now took on more risk of market price fluctuations from the pipeline certificates than it was willing to bear. Fortunate for Standard, its monopsony power allowed it to go back to paying producers for oil directly in cash without any risk of delivery, as the company now controlled 90% of the country’s refining capacity. This deemed the petroleum exchanges useless, and Standard proceeded to promptly purchased and canceled “all the certificates they could get” (Tennent, 1915, p. 15). With the futures market becoming increasingly illiquid, short selling became very dangerous, and brokers began to flee the business.

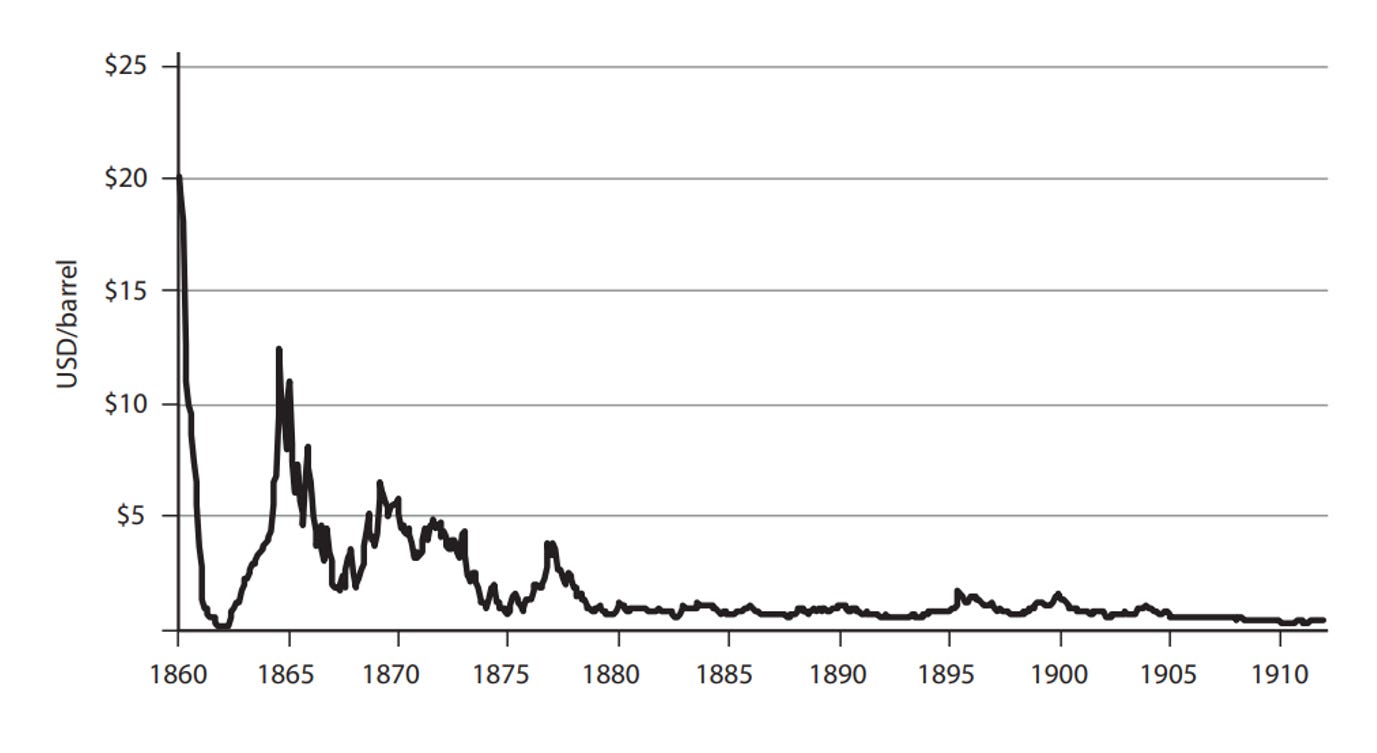

On January 23, 1895, Standard made the final blow to the oil futures market: its Pennsylvania purchasing wing Seep Agency, headquartered in Oil City, issued a memorandum to producers which stated that the “small amount of dealing in certificate oil on the exchanges”—illiquidity Standard Oil effectively guaranteed by canceling its own contracts—made “transactions there no longer a reliable indication of the value of the product” (reprinted in The Derrick’s Hand-Book, 1898, p. 775). Therefore, Standard would instead pay the “price as high as the markets of the world will justify, but not necessarily be the price bid on the exchange for certificate oil” (ibid.). Although some oil exchanges remained and diversified into other commodities (e.g. Pittsburgh Petroleum Exchange became Pittsburgh Petroleum, Stock, and Metal Exchange), this announcement from Standard Oil effectively took all pricing power for crude oil away from the exchanges and into its own “posted price” system. This, in turn, would dramatically stabilize US crude oil prices for the next several decades, until the Supreme Court-ordered breakup of Standard Oil in 1911, after which the “gusher years” would return again and dramatically increase oil price volatility.

Concluding…

One of the reasons I find this period of the oil industry so interesting is because of how it troubles our periodization of “financialization.” More specifically, Costas Lapvitsas (2013) has stressed that, although finance has been an essential moment in the circuit of capital since the Industrial Revolution, what is for him unique about the past 50 or so years is the increasing financialization of funds that were not rooted in surplus value and, in particular, the financialization of household income. As I have tried to show through this two-part post, “household income” was in fact a significant source of cashflow for oil financiers since the beginning, first, given the important of joint-stock companies and, second, given the participation of retail investors in the petroleum exchanges. Indeed, all of the kinds of market behaviors we tend to associate with the more recent futures market were already evident in this period: bears and bulls, ‘selling the news’, and even the avoidance of physical delivery by offsetting of equal and opposite paper trades.

Of course, crop futures trading exhibited the same behaviors, and “bucket shops” of the late 19th century had in turn likewise “brought futures to the masses” (Levy, 2006, p. 316). In both cases, then, the enrollment of household income into circuits finance capital since at least the 19th century ought to force a wholesale reconsideration of the history of financialization, as not only rooted in the buildup of idle capital but also, evidently, directly within wages.

References

American Transfer Co. n.d. Notes. Volume 2.207, Box J97a. ExxonMobil Historical Collection. Briscoe Center, University of Texas-Austin, Austin, Texas.

Barbour, John B. 1928. “Sketch of the Pittsburgh oil exchanges.” Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 11(3), pp. 127-143.

Bell, Herbert Charles. 1890. History of Venango Country, Pennsylvania, and Incidentally of Petroleum, together with Accounts of the Early Settlements and Progress of Each Township, Borough and Village, with Personal and Biographical Sketches of the Early Settlers, Representative Men, Family Records, Etc. Chicago, Brown, Runk & Co, Publishers.

Boyle, P.C. 1915. “Publisher’s Announcement.” In Tennent, James C. The Oil Scouts: Reminiscences of the Night Riders of the Hemlocks. Derrick Publishing Company, pp. 7-12.

Brown, John Howard, and Mark Partridge. 1998. “The death of a market: Standard Oil and the demise of 19th century crude oil exchanges.” Review of Industrial Organization 13, pp. 569-587. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007795128137

Derrick’s Hand-Book of Petroleum, The (Volume 1). 1898. Derrick Publishing Company, Oil City, PA.

Giebelhaus, August. 1977. The Rise of an Independent Major: The Sun Oil Company, 1876-1945. Dissertation, University of Delaware.

Helfman, Harold M. 1950. “Twenty-nine hectic days: Public opinion and the oil war of 1872.” Pennsylvania History 17(2), pp. 121-138. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27769103

Lapavitsas, Costas. 2013. Profiting without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All. London & New York, Verso.

Levy, Jonathan Ira. 2006. “Contemplating delivery: Futures trading and the problem of commodity exchange in the United States, 1875-1905.” The American Historical Review 111(2), pp. 307-335. https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.111.2.307

McNally, Robert. 2017. Crude Volatility: The History and the Future of Boom-Bust Oil Prices. New York, Columbia University Press.

Tennent, James C. 1915. The Oil Scouts: Reminiscences of the Night Riders of the Hemlocks. Derrick Publishing Company.

Weiner, Robert J. 2003. “Financial innovation in an emerging market: Petroleum derivatives in the 19th century.” Accessed at https://users.nber.org/~confer/2003/URCDAE03/weiner.pdf

The certificate system also gave pipe lines sufficient leverage against producers in the case of accident during storage, as evinced by a notice from American Transfer Company on October 31, 1872: “Notice is hereby given to patrons of the American Transfer Company that all losses sustained on oil on account of lightning, fire or other unavoidable cause will be charged to parties holding oil in the custody of the company, whether said oil is to their credit on the books of the company or in certificate, pro rate upon the principles of general average.” (American Transfer Co. notes, n.d).

Herbert Bell reports that this consolidation was motivated by heavy competition in 1876 between pipeline companies which “caused the business to be conducted without profit, and in some instances with great loss” (1890, p. 510). In 1877, United Pipelines to merge and acquire a series of other pipeline companies, including Antwerp & Oil City Pipe Companies, The Atlantic Pipe company, The American Transfer Company, the Sandy Pipe Line, The Empire Pipe Line, Columbia Conduit, American Transfer, Olean Pipe Line, Hunter & Cummings Line, Keystone Pipe Line, and the Relief Pipe Company, for a total capital stock of $5 million ($87 million in 2020 dollars). For a fascinating albeit obnoxiously bourgeois account of the conflict between oil region producers and a railroad and refinery conspiracy involving Standard, the “South Improvement Company,” see Helfman (1950).